19 Jul Interview with Christine Walley and Chris Boebel

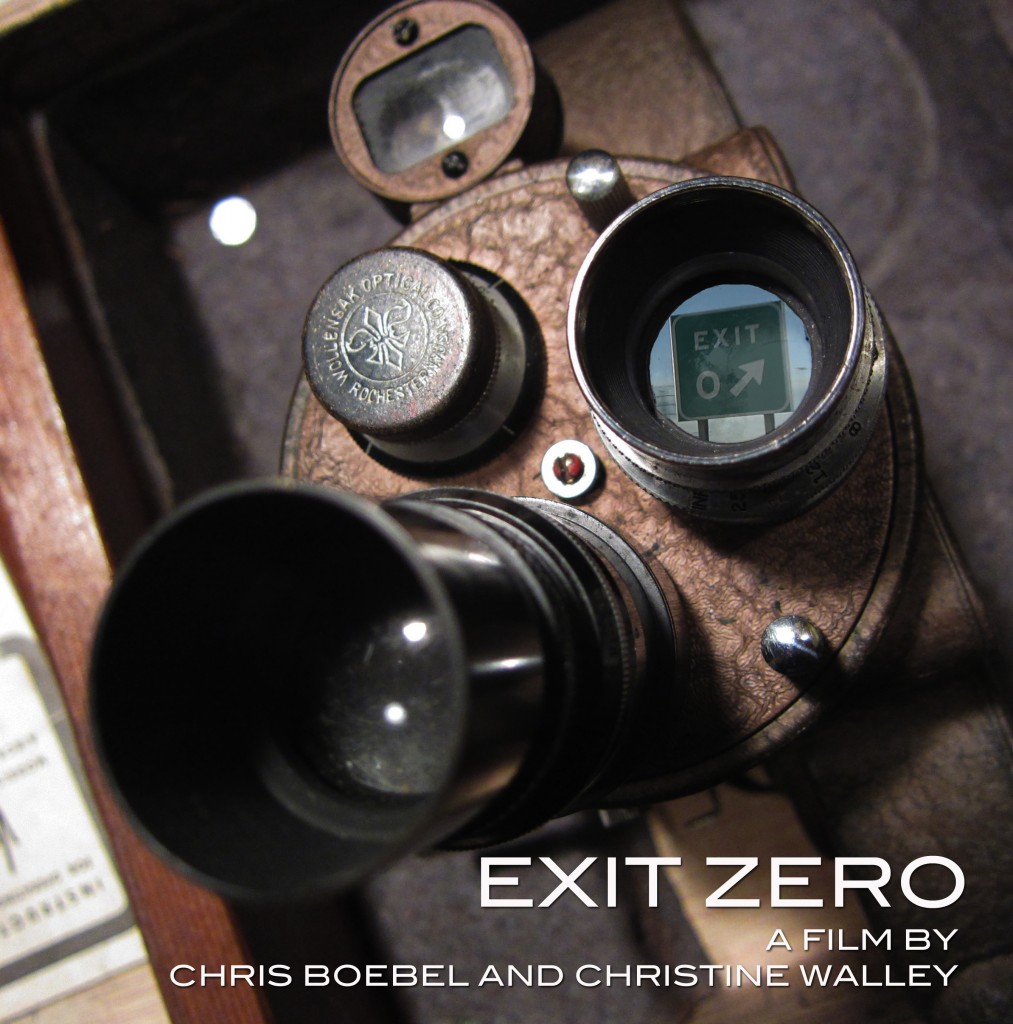

Christine Walley and Chris Boebel are documentary filmmakers and advisors to the Open Documentary Lab @ MIT. They are currently collaborating on Exit Zero, a documentary about one family’s experience of deindustrialization in southeast Chicago. Exit Zero is a cross-platform experience. Walley’s book, Exit Zero: Family and Class in Postindustrial Chicago is forthcoming from the University of Chicago Press, and Boebel and Walley are also developing an interactive web companion to the film and book.

Walley, an Associate Professor in MIT’s anthropology program, and Boebel, a director and writer, were kind enough to sit down with the OpenDocLab to discuss Exit Zero, as well as the potential of new documentary technology.

How did you become interested in documentaries? What do you find appealing about documentary as a mode of expression?

Chris Boebel: After college, I attended NYU’s Grad film program, where I – like most people there – was completely focused on narrative fiction filmmaking. I didn’t study documentary, I didn’t make documentaries. In fact, I didn’t really think seriously about them until a couple of years after I graduated. At that point, a few things happened – first, I saw a couple of Errol Morris’ early films – Gates of Heaven and Vernon, Florida. Second, at around the same time, I also saw for the first time a couple of classic documentaries from a very different genre – the “Direct Cinema” school – “Don’t Look Back” and “Primary.” And finally, I met Chris W., and she introduced me to some of the films of Jean Rouch. Although all of these documentaries were very different in style and approach, what they shared was a stunning ability to tell complex and very human stories. They were so much more engaging and powerful than most of the narrative films that I was watching – or that I saw being made around me. At that point, I decided sort of randomly that I wanted to start making documentaries too – something that Chris W. really encouraged me in, because it fits so well with the ethnographic work she was doing as an anthropologist.

I think what’s appealing about documentary filmmaking for me is that it’s a way of ensuring that as a filmmaker you don’t close yourself off in a protective cocoon or bubble. It forces you to stay engaged with human beings and human stories, and you’re continually required to adjust your approach towards – and your attitude about – the stories you’re trying to tell. It’s such an intellectually and emotionally engaging process.

Chris Walley: I also did my graduate work at NYU which is where Chris B and I met. The Culture and Media program in Anthropology had recently been launched by Faye Ginsburg, and there was a great deal of excitement about it. Almost all of my friends who were anthropology grad students were working on short documentary films, not from an older “ethnographic film” angle, but more from an ethnographic approach to everyday life as well as how and why people create media. However, I didn’t actually do the “culture and media” program myself – frankly, I think I was intimidated by the technical aspects of it.

I began to get involved in documentary filmmaking after meeting Chris B. After he began to get interested in documentaries in the late 1990s, Chris started working with Nick Poppy on a documentary film about the long-term impact of the Three Mile Island nuclear accident on the surrounding community. At first, I started going along on shoots and helping out as a production assistant. Later, I became an associate producer on the film. After I started teaching at MIT, Chris and I began working together on the “Exit Zero” documentary, and a few years later we started co-teaching “DV Lab” in the Anthropology Program which is a mixed documentary production and theory class.

To me, documentary film is both a creative and analytical way of engaging with the world. It’s about paying attention to what’s going on around us, and trying to create something that is simultaneously a form of storytelling and a form of analysis. In my own case, I see it as an extension of doing ethnography in other forms – in all cases there’s a kind of intensive engagement with the world in which we try to convey a certain perspective on, or interpretation of, whatever topic we’re exploring, even as we try to be as honest as possible and hold ourselves accountable to what’s “out there,” whether or not that fits our own preconceptions.

Can you talk a little bit about your current project, Exit Zero? What was the genesis? What themes and issues are you working to highlight? What challenges are you encountering?

CW: In a sense, I’ve lived with this project almost my entire life. Exit Zero is about the impact that deindustrialization has had on expanding class inequalities in the United States, but is told through the particular experiences of the old steel mill communities of Southeast Chicago where I was raised. Both my mother and father had deep family ties in the area. I was 14 when the steel mill where my father worked shut down, and it had a traumatic impact upon my own family. As the rest of the steel mills in the area started to close, one by one, the regional economy was devastated. Even thirty years later, Southeast Chicago hasn’t recovered and is now filled with massive empty industrial brownfields.

I’ve always felt a profound need to understand what had happened to Southeast Chicago and other places like it – and what deindustrialization has meant for the United States more generally. In the end, I decided to do this work in a more personal and less overtly academic way – although hopefully the project retains a good deal of useful analysis as well. Basically, the book uses family stories to explore issues of social class and deindustrialization. During the time I was writing my book Exit Zero: Family and Class in Post-Industrial Chicago (forthcoming, University of Chicago Press, 2012), Chris B and I were also working on the documentary – although in fits and starts. The film and book are simultaneously separate works and completely bound up with the other. The vision for the film has been more that of my husband, Chris B, than my own, even though the voice in the narration is mine. In many ways, our voices and ideas have become completely intertwined over the years of working on these projects, but the clarity to see how to tell the story in visual terms has really come from Chris.

CB: Chris and I have known each other since 1994. Soon after we met, I travelled to Chicago with her to meet her family for the first time. At that point, even 15 years after the closure of Wisconsin Steel, the wounds of that experience were still very fresh – particularly for her Dad. It was such an emotionally wrenching – but also emotionally vivid – environment to drop into. I felt immediately that Chris’s family’s story – and the neighborhood’s – was a really important story to try to tell. In fact, I remember at some point on that trip driving down the “Exit 0” ramp for the first time, and saying to Chris – maybe somewhat facetiously – “we need to make a movie about this place, and we need to call it Exit Zero.”

At that point, I was probably thinking of some kind of low budget independent fiction film. Ten years later, when we finally started shooting something, it thankfully had become a documentary. But at that point, I think what we both imagined was a somewhat more “traditional” interview-driven film. Our idea was to interview her family, neighbors, and other community members extensively, and then cut together a sort of pastiche portrait of the area – sort of like what “Containment” was for the community around the Three Mile Island plant. Almost immediately we ran into the difficulty that her Dad wouldn’t sit down with us for a formal on-camera interview. But whenever I took out the camera, he would seek me out, and start talking to me. He wanted to tell his story, but also not tell it – and that reticence about, but simultaneous need to, speak became a central motif of the film. At some point we also realized that all the hanging out we were doing in between interviews was just as – or more – interesting than the interviews themselves. So the film slowly turned into a far more personal story about Chris and her family in which the need to make the film itself – to speak about the past – is a key theme.

What can media makers working with new documentary forms learn from the history of the medium? Do past experiments in documentary filmmaking inform present innovation?

CW and CB: We both feel that long-form documentary film is not going to be replaced by newer online interactive documentary projects. Instead, we think it will serve as a complement or will do something different that expands upon – rather than replaces – our conceptions of what documentary is. We’re in the planning stages right now of a participatory online documentary project for Exit Zero being made in collaboration with MIT’s Open Doc Lab as well as with a tiny all-volunteer museum called the Southeast Chicago Historical Museum. Our goal is to create a website that can serve both as a usable online historical archive for the rich but difficult-to-access materials in this tiny museum as well as a storytelling platform. We’re hoping that the museum artifacts on the website will provoke viewers to tell their own stories regarding issues of social class, or experiences with deindustrialization, or immigration, or other related topics, in ways that parallel what we have tried to do with the Exit Zero film and what I tried to do in the book.

Certainly, the participatory aspects of newer online forms of documentary have precursors in older documentary formats. For example, anthropological filmmaker Jean Rouch, not only often worked collaboratively with his subjects, but, in films like Jaguar, the storylines were improvised. Rouch’s understanding, drawing upon surrealism, was that getting at people’s hopes and dreams – which improvisation can help access – allows one to capture deeper “truths” than simple observation with a camera. In other words, to “document” the complexity of people’s lived experiences you have to move beyond the observable into the inner spaces of their psyches and souls and their own self-understanding. Personal narration is another way to dig “deep” in that kind of way. But, again, documentary formats have to simultaneously be paired with a scrupulous honesty about letting the world talk back to us and shake our own self-understandings.

Our hope is that those interested in new media forms of documentary filmmaking will find much food for thought as well as interesting techniques in the older documentary film canon.

As scholars and practitioners, you have a unique perspective on documentary form and innovation. In your opinion, what storytelling possibilities—and challenges—are created by new technologies? How might media makers work across a range of platforms and formats to expand the possibilities for documentary work?

CB and CW: The newer formats open up lots of possibilities – for accessibility in ways that would have been beyond reach for many standard documentaries. They are also exciting in that they allow for a different kind of participatory involvement on the part of audiences and different ways of playing with narrative that are about telling stories in non-linear ways. But, at the same time, one of the challenges is that it can be harder to get people to emotionally invest in a non-linear story rather than to just surf over something. There have been some fascinating projects that have emerged in these new formats, particularly in the terrific work of the National Film Board of Canada; in general, however, the possibilities and limitations of these new documentary forms still remains to be seen. We’re most excited about the possibility of narratives that move across genres, morphing in the process to take advantage of one form’s particular strengths – so with Exit Zero, you can start with Chris W’s book, with its social analysis of class and the impact of deindustrialization, to the linear documentary, with its focus on family history, relationships, and narratives, and on into (hopefully!) the world of interactive storytelling that has the potential to open up the participatory experience for audiences in new ways.

Posted by Katie Edgerton/MIT