The Guardian

Digital-First Vanguards in News Media

Academic and journalist Emily Bell left her old job at The Observer in 2001 for a post at The Guardian in order to “work on the Web.” When she told others about her plans to become executive editor at the Media Guardian website, she recalls, “People actually thought that I had been sacked.”1 While few at the time understood the potential of the Web, The Guardian had a core team of people who did, with Bell among them. This team also understood that the technical expertise required to work on the Web did not just entail coding or web design, but “it also meant understanding, almost implicitly, user behavior” on the Web and creating a strategy around it.2 This ethos of experimentation is what allowed The Guardian to transform itself into a digital-first institution early on, and, more specifically for this report, what allowed The Guardian to break away from traditional storytelling methods and experiment with storytelling “of the Web.”

With a consistent output of interactive digital documentary projects, a bold attitude towards digital innovation, and a profound understanding of the Web, The Guardian’s digital beginning is a story in itself worth telling. What was it about The Guardian that enabled such experimentation? How did a legacy news organization navigate the transition into a digital news outlet? In this case study, we explore these questions and more, with a particular focus on interactive documentary projects (or “interactive features,” as they are called at The Guardian).

Auspicious beginnings

The Guardian first launched its online presence in September of 1995. Its New Media Lab was established by the Board of Guardian Newspapers, Ltd., with the intent of publishing content electronically.3 By 1999, the site had one million registered users, and its network of news websites, Guardian Unlimited (rebranded as guardian.co.uk in 2008), was receiving 10.2 million page impressions per month.4 The site went on to win multiple Web awards, including Best Design for an Interactive Newspaper at the U.S. Eppy Award, Best Newspaper on the Web in the Newspaper Society Awards, and Online News Service of the Year at the British Press Awards.5 It was clear that the digital work The Guardian had been producing was being recognized among peers.

According to Bell, The Guardian understood what it meant to be “of the Web” and not just “on the Web.” With the Web as a platform, news organizations could now be in direct conversation with their readers and return to what Bell considers one of journalism’s central roles: to create and connect communities. In 2006, under Bell’s leadership, The Guardian launched Comment is Free,6an “open-ended space for debate, dispute, argument and agreement” and one designed “to invite users to comment on everything they read.”7 The site contains comment and op-ed pieces from The Guardian and The Observer as well as contributions from citizen writers. Discussion about the articles is encouraged, but the site also moderates comments before posting in some cases. With this initiative, The Guardian committed to open journalism,8 a type of journalism that encourages audience interactions with news content. Other, similar initiatives also emerged, such as Guardian Witness,9 a tool for user-generated content (UGC) built right into the company’s content management system, which enables any journalist to access and use it in her or his stories, and Contributoria,10 a division of the Guardian Media Group, which allows anyone to propose a story, to receive community feedback, and to have the chance to be published in The Guardian. The company also made a habit of opening up editorial meetings to anyone in the organization, not just to editorial staff.

The Guardian’s financial structure also enables more freedom to innovate. It is owned by The Scott Trust, a private company and the sole shareholder in the Guardian Media Group. It was founded in 1936 as a trust and exists to secure the financial and editorial independence of The Guardian in perpetuity.11 The shareholders of the trust take no dividend from the business. While profit is important, there is not as much pressure to make an immediate profit, which has allowed The Guardian to take risks both with content and form. This freedom, together with leadership’s insight and vision, has allowed The Guardian to forge ahead in the digital terrain. In fact, in 2011, despite a £33 million loss in profit and a media economy that was increasingly oriented toward the Internet, The Guardian announced its major strategy to transform into a digital-first organization.12

Separation of form and content

One of the most important shifts in mindset at The Guardian came in the form of the separation of form and content, “which now seems absolutely obvious,” says Bell, “but at the time seemed revolutionary.”13 The legacy mindset involves content being released in one form: print. However, digital media offer myriad ways in which to tell a story, prompting a shift in thinking about how stories might take shape online—a shift that may have been facilitated by the 2012 release of Snow Fallf rom The New York Times.14

Snow Fall is a digital news story about the February 2012 Tunnel Creek Avalanche in the Washington Cascades of North America (see Figure 1). The story integrates video, images, and text in a way that “makes multimedia feel natural and useful, not just tacked on,” reports Rebecca Greenfield, from The Wire.15 The reader scrolls through the story encountering text and multimedia components seamlessly woven together. At the time it was released, there were not many other examples of news projects that created this seamless flow between text and multimedia. In fact, Snow Fall is credited by many in the field with ushering in a new kind of web aesthetic known as “scrollytelling”—enabling the viewer to scroll through a story and its multimedia components as opposed to clicking through them. Since Snow Fall, scrollytelling has become a norm in many digital newsrooms as a technique that creates a more immersive experience. The Wire’s Greenfield is one of many onlooking journalists who heralded Snow Fall as a success that pushed the boundaries of how the public perceives digital journalism. The form and format of Snow Fall deviated from what audiences were used to and elicited a sense of a narrative “experience.” This was, of course, deliberate.

Figure 1. Screenshot of “Snow Fall.” Source: http://www.nytimes.com/projects/2012/snow-fall/#/?part=tunnel-creek.

The New York Times (NYT) Graphics Director Steve Duenes talks about collaboration between the reporter, graphics editor, sports editor, and others involved as a key component for such an integrated piece. “As [author John Branch] started to write, we were looking at drafts and thinking about the places where it made sense to embed something,” Duenes told The Poynter Institute.16 “The multimedia plus the story were moving along parallel tracks. We were communicating often as things were progressing,” he said.17

Andrew DeVigal, head of the multimedia department at the time, explains that the collaborative process was the true innovation in Snow Fall. The idea for the piece originated when Duenes and DeVigal approached Sexton, the NYT’s sports editor, in the summer of 2012, suggesting an integrated storytelling approach to blend text, picture, and graphics to the next level.18 Snow Fall seemed like the appropriate story for this experiment. They suggested bringing in the multimedia, graphics, and photo teams from the beginning to work with Branch and his editors; the decision to be collaborative at that level was the innovation. Together they decided when text content could better be described with visuals. It was this collaborative process that created the seamless, immersive, and integrated storytelling for which Snow Fall is known.

Although the end result stimulated much dialogue about the future of journalism, Aron Pilhofer, executive editor of digital for The Guardian, who was working at The New York Times when Snow Fall was produced, is quick to point out that such innovations are driven by a functional need. In the case of Snow Fall, Steve Duenes, who commissioned the piece, had a 19,000 word essay. “You can’t just put 19,000 words in a standard article template,” Pilhofer says.19 “[Snow Fall] was serving a purpose.”20 Pilhofer worries that the lesson many learned from Snow Fall was to inject more “zazz” into news pieces, tacking on flashy features and interactivity to stories and consequently distracting from the content.21 At the end of the day, Pilhofer insists, the right approach is to start from the point of view of the story that needs to be told, then to work on the format: “If it wants to be a big interactive thing, it will be,” Pilhofer says.22

For news organizations—digital or not—Snow Fall was a watershed moment, leaving newspapers to figure out how they fit into a changing media environment. As new, interactive storytelling forms and processes began to emerge, skeptics raised questions about whether these interactive forms, which took significantly longer to design, develop, and deploy, could exist in tandem with breaking news, which worked on a completely different time frame. Then something happened that changed the game again. This time, The Guardian was at the helm.

The Guardian’s NSA Files: Decoded23 came out on the heels of Snow Fall. The story weaved together complex political, legal, and technological questions about NSA documents revealed by Edward Snowden. It also employed a variety of media (video, interactive graphics, maps, charts, text, and GIFs) to guide the reader through the story. The goal of the piece was to answer one important question for the reader: what do these NSA revelations mean for me? (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2. Screenshot of “NSA Files: Decoded.” Source: http://www.theguardian.com/world/interactive/2013/nov/01/snowden-nsa-files-surveillance-revelations-decoded#section/1.

NSA Files: Decoded relied heavily on video seamlessly interwoven with graphics and text to tell the story. “It takes an extremely flexible reporter” to cede that kind of control, says Gabriel Dance, who was the interactive editor of NSA Files: Decoded.24 The video also started automatically as soon as a user landed on it, an innovative technique that created a more seamless experience.

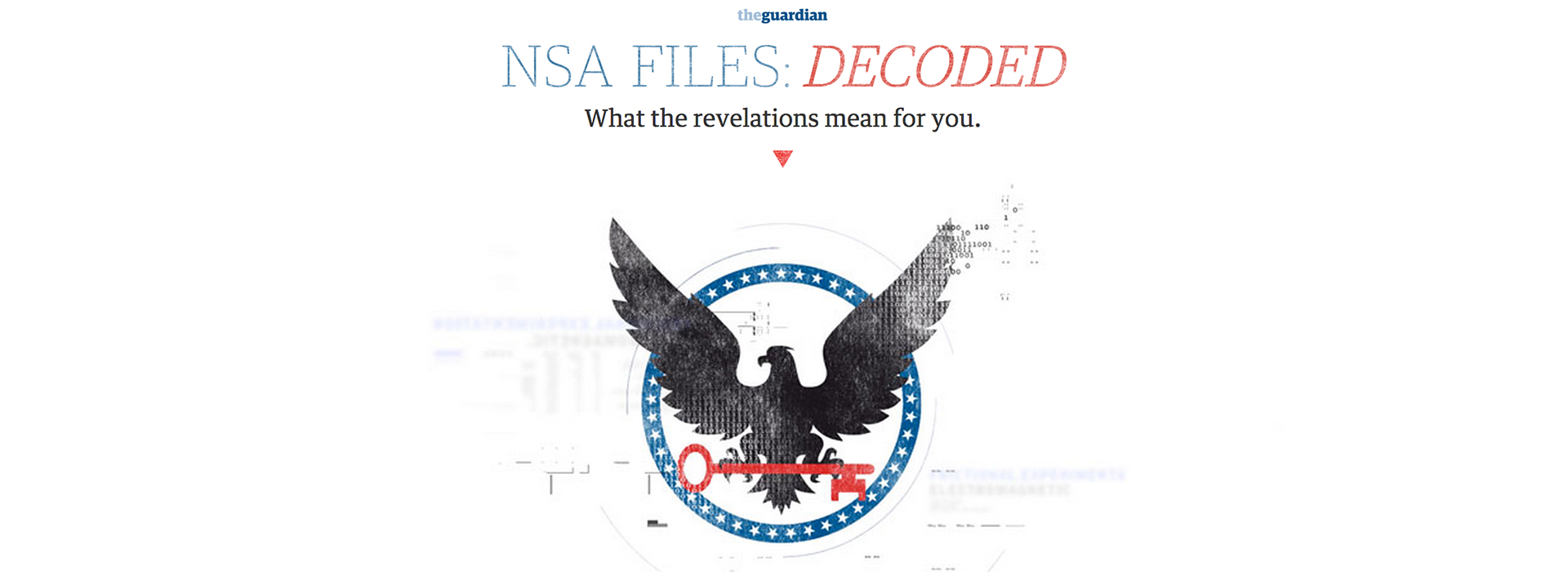

NSA Files: Decoded, was a product of The Guardian (U.S.), which had been set up as a lab for The Guardian to experiment with Web-only journalism. Dance, who has dual degrees in journalism and engineering and had just finished a four-year stint at The New York Times, was charged with creating “explainer” stories to contextualize the news. Given the complex nature of the NSA materials, Dance confronted the challenge of finding the best way to break down the information in explainer style content. In the end, Dance suggested video interviews where the experts directly address the public. In the interviews, shot by Bob Sacha, the interviewees appear to be looking directly at the reader, breaking the fourth wall and rendering the overall experience more immersive. Key experts, including U.S. Senator Ron Wyden, Congresswoman Zoe Lofgren, NSA whistleblower Thomas Drake, and ACLU lawyer Jameel Jaffer, appear in the videos in order to translate NSA policy into more colloquial terms (see Figure 3). The project took two months of work and the team responsible for it comprised three people, including Dance.

After the story was released, audiences spent an average of thirty minutes on the site, according to Dance—unheard of in the digital news world.25 With NSA Files: Decoded, The Guardian demonstrated how a small, interdisciplinary team could create a custom media experience that made use of video, graphics, text, and interactive features to immerse and engage audiences in unprecedented ways.

Figure 3. Congresswoman Zoe Lofgren and other key figures appear in “NSA Files: Decoded.” Source: http://www.theguardian.com/world/interactive/2013/nov/01/snowden-nsa-files-surveillance-revelations-decoded#section/1

Firestorm, released in 2013, is another story from The Guardian that combines multimedia features (see Figure 4). Even more than NSA Files: Decoded, Firestorm deviates from print by using video and photos as the backbone of the story. In six chapters, the story follows the life of a family in Tasmania hiding from a devastating and violent bush fire. Every scroll downward takes the reader to another slide or screen, which uses one of several forms of media to advance the story. Text appears in short paragraphs or in sidebars. Many of the screens feature a video or audio clip of the bush fire and interviews with the family. Static images appear as background when video does not (see Figure 5).

Figure 4. Screenshot of “Firestorm.” Source: http://www.theguardian.com/world/interactive/2013/may/26/firestorm-bushfire-dunalley-holmes-family. .

Figure 5. Screenshot of map of fire service response in “Firestorm.” Source: http://www.theguardian.com/world/interactive/2013/may/26/firestorm-bushfire-dunalley-holmes-family.

Both Firestorm and NSA Files: Decoded represent significant departures from traditional print journalism, yet they are emblematic of the kind of institution into which The Guardian early on aspired to transform itself—one that prioritized story over storytelling medium.

Of course, with new, experimental projects, there came new ways of working within the newsroom. Not all interactive documentary projects have the luxury of a nimble, interdisciplinary team, and not all projects can be turned around so quickly. In order to ensure that NSA Files: Decoded, Firestorm, and a few others would not be the exception to the norm, new roles, tools, and workflows needed to be established to sustain the work of interactive storytelling at The Guardian.

New roles, tools, and flows

An important question for any newsroom revolves around how to create interactive documentaries in an environment that privileges the daily news cycle. Interactive documentaries take time and resources; all the while, daily news still needs to be reported swiftly and accurately. These conflicting timeframes pose a unique challenge and point to a key tension in the intersection of journalism and interactive documentary forms.

Multimedia Special Projects Editor Francesca Panetta had originally been hired by The Guardian in 2006 as an audio producer, but, once there, she found herself gravitating towards other media and technologies.26 In 2011, after she created a geo-located audio map,27she asked The Guardian for the special projects editor position. They agreed. Lindsay Poulton was assigned as Panetta’s film producer, and Panetta was told that she could draw on The Guardian’s resource of multimedia producers, developers, designers, and writers, “within reason.”28 In these early days, she says, it was difficult to discern what “within reason” truly meant when it came to pulling staff away from their priorities.29 Still, Panetta became used to working around people’s schedules and was even given a small budget to hire freelancers. She also learned to rely on collaborations with other institutions. In short, she used a combination of in-house resources, freelancers, and co-productions to get the work done. Panetta was the editor who oversaw The Guardian’s Firestorm, along with other interactive, media-rich stories such as The Shirt On Your Back, World War I, and Seven Deadly Digital Sins.30 Although she was averaging two to three interactive feature projects a year, the work was largely ad hoc, without a regular, consistent team assigned to do interactive projects.

It’s Panetta’s job to figure out what a story is meant to do and what it should look like. She is responsible for making projects for The Guardian that showcase the organization’s storytelling innovation. Her work often shows up at the top documentary film festivals and wins awards. Unlike documentaries made in film institutions or independently, her projects are completed in one year or less. An integral part of this process is developing a key understanding of what the story is, how to tell it, and who will help to get it done.

Pilhofer, who had previously worked for The New York Times as associate managing editor for digital strategy, moved to The Guardian office in London to create new teams in the newsroom that would be more conducive to interactive storytelling, particularly on the Web and mobile devices. He had heard about Panetta’s work, and his aim was to make the production of interactive stories more fluid and more integrated into “business as usual.”31 When Pilhofer arrived, there was only a small interactive team. He hired eight new developers and designers and named this group the visuals team, modeled after National Public Radio (NPR)’s interdisciplinary news team of the same name. In addition, Pilhofer hired new special projects editors to cover specific beats, such as business, national, international, features, and sports. These editors also serve as bridges between the visuals team and the rest of the newsroom, and they can serve as sounding boards for reporters with digital storytelling ideas. That way, by the time an idea gets to the visuals team, it will have already made it through an editor in the newsroom.

“It’s actually very, very easy now to assemble a team that has the right skills on them,” says Pilhofer.32 “In order to do those kinds of projects, you need to assemble teams that have different disciplines. You might need a coder-developer, data viz, photographer, etc. Trying to do that within a very rigid desk structure is incredibly difficult,” he says.33 Pilhofer wanted to create an environment in which those combinations could form for different projects while maintaining a certain amount of autonomy within traditional desk structures. Each of the desks still has its individual editor, maintaining its autonomy in that sense, but when someone wants to assemble a multidisciplinary team, a visuals team editor sitting on top can make it happen. And when asked about the expense of multimedia storytelling, Pilhofer explains that it’s an opportunity cost rather than an actual cost, a matter of choosing where you want to put your resources.34

A separate challenge for The Guardian’s Panetta as a multimedia special projects editor has been clarifying her role to her colleagues in the newsroom. When she first started, she says, though many journalists wanted their stories turned into interactive features, they had little knowledge of the process it entailed.35 “When multimedia started in the newsroom, there was this idea that you were very technical,” she recalls.36 “People would come up and ask, ‘Well, can you just film this? Can you make a podcast on this?’ That somehow you were just technical operators,” Panetta says.37 Film producer Poulton adds that there is a lot of confusion over what the role of a multimedia creator is, but “that’s okay,” she says.38 “I think a lot of our job is about explaining not only what the new form is, but also what you expect from people.”39

Panetta feels that most of these early assumptions have been debunked by now. Having technical skills no longer means just the ability to operate technical equipment but also the ability to connect the dots and orchestrate various types of media production. “I think now within our department they consider me editorially and creatively competent to make and look after these projects,” she says.40 She also thinks that the advent of the visuals team has made her role even clearer.41

Gabriel Dance, formerly at The Guardian and now a managing editor at The Marshall Project, has hired journalists and designers with programming skills, and designers and developers with an understanding of story. Like Pilhofer, he is trying to create teams and environments in which collaborative projects are part of the status quo: “Collaboration is bigger than it ever has been in newsrooms, and only continues to grow more important…. You just can’t do it as one person.”42 Dance is also trying to make it easier for his team to build interactive documentary projects, which in part requires lowering the technical threshold. One way he has done this is by custom-building The Marshall Project’s content management system to include many tools that make it very easy to create media-rich, immersive storytelling. When asked why he is focusing his efforts on this, he responds:

Content management systems, for the most part, and certainly amongst traditional media agencies, are heavily based on copy. They’re based on producing written stories. Then, slowly, we’ve seen it become a little easier. You get these embeddable video widgets, and then you could drop photos in. If your CMS can do that easily, you’re in a good spot. …In order to be able to make multimedia storytelling a much more robust and valid opportunity at The Marshall Project, we need to think about building those types of projects to make them as easy as possible. The goal here is that those storytelling methods will be built into the system in the same way that photos are built into the system, and in the same way the copy is built into the system.43

Dance insists that improving technology allows creators to focus more on the story. This, he believes, is best so that the story can be told in a way that resonates with people. “[The tools] need to be flexible. The way you approach [them] needs to be flexible. Every story should be told on its own terms with the tools available to do so,” Dance says.44 There will always be big, important, bespoke projects, such as NSA Files: Decoded, where the story requires customization; but with a more adaptable content management system, both these stories and smaller features will be more possible.

Developing and measuring digital audiences The emergence of digital storytelling has changed The Guardian’s news culture’s relationship to its audience. Pilhofer stresses the importance of starting from the point of view of the reader and working backwards, a basic principle of human-centered design and an intended shift from what Pilhofer calls “the publish and pray” school of journalism.45 As a result, audience development teams, tools, and processes are now an integral part of the digital newsroom.

Once kept separate from editorial teams, audience development teams at The Guardian now work hand in hand with journalists to test and interpret audience behavior, so editors can make more informed decisions about what to publish. Otherwise it’s difficult for editors to know what to do in the digital environment, according to Pilhofer.46

Chris Moran, head of the The Guardian’s audience development team, told Journalism.co.uk, “We know everything about print, pretty much, there’s not many tricks left in the bag, we’ve done it for 200 years and we’re used to it. But the internet’s changing all the time, as much as anything else.”47

Pilhofer explains that the tendency at many institutions is to try everything. “[Newsroom editors and reporters] don’t know what to do,” explains Pilhofer.48 “More importantly, they don’t know what not to do. The natural instinct is to just kind of throw everything at it and hope. That’s being digital. It’s totally not their fault; they just don’t have any way to know.”49 The Guardian has set out to ensure that they do have a way of knowing.

The audience development team helps journalists understand who their audience is, how that audience consumes content, how to publish content in ways that reach the audience, and how to measure audience reach and impact. To do this, the newsroom relies on a combination of tools and testing.

One new tool built by the audience development team is called Ophan, an in-house analytics engine. According to a FastCompany article by Ciara Byrne, Ophan looks at attention analytics and tracks all of The Guardian’s traffic, giving the journalists and editors who use it insight about which stories are performing best.50 Ophan makes its data available to “400 journalists, editors, and developers with a time-lag of less than five seconds.”51 The data can also be filtered by “country, time period, section, mobile app and devices, browsers, referral sources, and more,” Byrne reports.52 According to The Guardian’s Moran, the idea is to “democratize data” so that journalists can easily understand how their stories are performing.53 The Guardian journalists are advised to look at referrals from different social media platforms, plus page views and attention time. The Guardian is less interested in Facebook likes and Twitter retweets because it wants to know whether people are actually reading the article or engaging with the interactive feature. Graham Tackley, Director of Architecture at The Guardian and creator of Ophan, told Journalism.co.uk, “It’s easy to rely on shares, ‘likes,’ and retweets to measure the effectiveness of something.”54 But, he added, “I’m always nervous about that, because I’d rather actually know how many people read the article. ...Those things are important to help us understand what’s really doing well, rather than what’s just generating tweets.”55

Through this internal analytics engine, The Guardian’s reporters and editors can measure attention time on media and see how long people engage with an interactive. Pilhofer cites as an example American Civil War Then and Now and the toggle that was created to move from an old photo to a new photo.56 The journalists could see that the toggle was intuitive and that people stayed on the site for an average of three minutes, a noteworthy amount of time for an interactive. Using Ophan, journalists and editors also have the capability to wire up different components and test them, and they can even test the impact of changes to the user-interface and “whether they drive engagement or not.”57 This kind of information allows the journalists and editors to decide, for example, what elements from one-off projects to spin into templates. By doing this, story templates start to become signature styles of The Guardian’s interactive stories.

Tools like Ophan reveal what is now possible to do in newsrooms once stories are released. User testing is a method that The Guardian uses to understand its audience before story creation. The idea of user testing relies on assessing whether the intended audience will respond favorably to a product. In this case, the product is a digital story or a component within it. The Guardian has a user testing lab in its main London office, where editors including Panetta conduct user testing regularly. This involves anything from talking to readers about story ideas, to finding out what topics and features most interest readers before production even begins. Sean Clarke, another special projects editor, relied extensively on user testing to determine how The Guardian would cover the U.K. elections and what would be of interest to people. Pilhofer explains, “He’s testing these basic assumptions. I mean that’s kind of a core tenet of user-centered design, where you start with problems actual people have, and then you try to solve them. That to me is a fundamental way that we want to approach what we do.”58 Both quantitative and qualitative testing methods are used, such as surveys, questionnaires, and tracking tools. A combination of tools like Ophan and methods like user testing helps the visuals team make editorial decisions about what to cover and how.

By now, conversations at The Guardian about what desk heads need to know have already happened; editors are now trained to know what should be tracked, how to assess whether stories are reaching target audiences, and what other points are needed in order to make decisions. Next, The Guardian is interested in defining and tracking metrics that give insight on depth of engagement (i.e. the chance that a person becomes a regular reader of The Guardian after having logged into the site once) as opposed to just scale (i.e. number of people who have looked at a story). By focusing on how to attract deeper engagement from readers, The Guardian is, by proxy, able to strategize about how to grow its membership.

Conclusion

The Guardian has transformed itself from a small but influential daily newspaper to a global digital platform with a record-breaking 120 million unique browsers (in January 2015), boasting one of the largest global audiences among English-language newspaper websites.59 As an institution, The Guardian has been able to successfully pivot towards a digital-first strategy, while letting story and audience dictate form and not the other way around. With the vision of people like Pilhofer, Panetta, Poulton, and Dance, The Guardian has been able to contribute an extensive repertoire of exemplary interactive features to the field of digital journalism.

On one hand, this pivot toward digital was something that needed to be done in order for The Guardian to survive as a news organization in the 21st century. On the other, it is a strategic and bold step—at the right time and with the right interdisciplinary teams—toward the future of media and interactive storytelling. It is this core ethos of experimentation and a willingness to venture into new territory—when few others had before them—that enabled The Guardian to transition from pen and paper to copy and code, leading the way as vanguards of digital news media.

1. Megan Garber, “‘Of the web, not on it’: Emily Bell on the success of The Guardian and what she plans for the Tow Center,” NiemanLab, 4 April 2011 [http://www.niemanlab.org/2011/04/of-the-web-not-on-it-emily-bell-on-the-success-of-the-guardian-and-what-she-plans-for-the-tow-center/]. ↩

2. Ibid. ↩

3. “History of the Guardian Website” (2014) [http://www.theguardian.com/gnm-archive/guardian-website-timeline]. ↩

4. Ibid. ↩

5. Ibid. ↩

6. “The Guardian Opinion” (2015) [http://www.theguardian.com/uk/commentisfree]. ↩

7. “History of the Guardian Website” (2014) [http://www.theguardian.com/gnm-archive/guardian-website-timeline]. ↩

8. Matthew Ingram, “Guardian Says Open Journalism is the Only Way Forward,” Gigaom, 1 March 2012 [https://gigaom.com/2012/03/01/guardian-says-open-journalism-is-the-only-way-forward/]. ↩

9. “Guardian Witness” (2015) [https://witness.theguardian.com]. ↩

10. “Contributoria” (2014-2015) [https://www.contributoria.com/]. ↩

11. “The Scott Trust: Values and History,” The Guardian, 26 July 2015 [http://www.theguardian.com/the-scott-trust/2015/jul/26/the-scott-trust]. ↩

12. Dan Sabbagh, “Guardian and Observer to Acquire ‘Digital First’ Strategy,” The Guardian, 16 June 2011 [http://www.theguardian.com/media/2011/jun/16/guardian-observer-digital-first-strategy]. ↩

13. Garber, 4 April 2011. ↩

14. John Branch, “Snow Fall,” The New York Times, December 2012 [http://www.nytimes.com/projects/2012/snow-fall/#/?part=tunnel-creek]. ↩

15. Rebecca Greenfield, “What the New York Times’s feature ‘Snow Fall’ Means to Online Journalism’s Future,” The Wire, 20 December 2012 [http://www.thewire.com/technology/2012/12/new-york-times-snow-fall-feature/60219/]. ↩

16. Jeff Sonderman, “How the New York Times Snow Fall Project Unifies Text, Multimedia,” Poynter, 20 December 2012 [http://www.poynter.org/news/mediawire/198970/how-the-new-york-times-snow-fall-project-unifies-text-multimedia/]. ↩

17. Ibid. ↩

18. DeVigal cites Pitchfork’s “Glitter in the Dark” [http://pitchfork.com/features/cover-story/reader/bat-for-lashes/] and ESPN’s “The Long Strange Trip of Dock Ellis” [http://sports.espn.go.com/espn/eticket/story?page=Dock-Ellis] as inspiration. ↩

19. Interview with Aron Pilhofer, London, U.K., 21 November 2014. ↩

20. Ibid. ↩

21. Ibid. ↩

22. Ibid. ↩

23. Ewen Macaskill and Gabriel Dance, “NSA Files: Decoded,” The Guardian, 1 November 2013 [http://www.theguardian.com/world/interactive/2013/nov/01/snowden-nsa-files-surveillance-revelations-decoded#section/1]. ↩

24. “The New Reality: Exploring the Intersection of New Documentary Forms and Digital Journalism,” MIT Forum, Cambridge, MA, 10 October, 2014 ↩

25. Justin Ellis, “Q&A: The Guardian’s Gabriel Dance on new tools for story and cultivating interactive journalism,” Nieman Lab, 25 November 2013 [http://www.niemanlab.org/2013/11/qa-the-guardians-gabriel-dance-on-new-tools-for-story-and-cultivating-interactive-journalism/]. ↩

26. Interview with Francesca Panetta, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 23 November 2014. ↩

27. “Streetstories” (2012) [http://www.theguardian.com/mobile/streetstories]. ↩

28. Panetta, 23 November 2014. ↩

29. Ibid. ↩

30. Seven Deadly Digital Sins was a collaboration with the National Film Board of Canada. ↩

31. Pilhofer, 21 November 2014. ↩

32. Skype interview with Aron Pilhofer, Cambridge, MA, 10 July 2015. ↩

33. Ibid. ↩

34. Ibid. ↩

35. Panetta, 23 November 2014.. ↩

36. Ibid. ↩

37. Ibid. ↩

38. Interview with Lindsay Poulton, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 23 November 2014. ↩

39. Ibid. ↩

40. Panetta, 23 November 2014. ↩

41. Email correspondence with Francesca Panetta, 17 August 2015. ↩

42. Phone interview with Gabriel Dance, Cambridge, MA, 22 June 2015. ↩

43. Ibid. ↩

44. Ibid. ↩

45. Pilhofer, 21 November 2014. ↩

46. Pilhofer, 10 July 2015. ↩

47. Abigail Edge, “How Ophan Offers Bespoke Data to Inform Content at the Guardian,” Journalism.co.uk, 2 December 2014 [https://www.journalism.co.uk/news/how-ophan-offers-bespoke-data-to-inform-content-at-the-guardian/s2/a563349/]. ↩

48. Pilhofer, 21 November 2014. ↩

49. Ibid. ↩

50. Ciara Byrne, “How The Guardian Uses Attention Analytics to Track Rising Stories,” Fast Company, 6 February 2014 [http://www.fastcompany.com/3026154/how-the-guardian-uses-attention-analytics-to-track-rising-stories]. ↩

51. Ibid. ↩

52. Ibid. ↩

53. Edge, 2 December 2014. ↩

54. Ibid. ↩

55. Ibid. ↩

56. “The American Civil War Then and Now,” The Guardian, 22 June 2015 [http://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/ng-interactive/2015/jun/22/american-civil-war-photography-interactive]. ↩

57. Pilhofer, 10 July 2015. ↩

58. Pilhofer, 21 November 2014.. ↩

59. “Guardian Reports Record Traffic to Start 2015,” GNM Press Office, The Guardian, 19 February 2015 [http://www.theguardian.com/gnm-press-office/2015/feb/19/guardian-reports-record-traffic-to-start-2015]. ↩