Collaborations In Interactive Documentary

Modeling Collaboration Across, Within, and Outside of Newsrooms

As our study examines how interactive documentary and journalistic forms converge and overlap, it also investigates the role of collaboration within this space. More recent interactive storytelling projects require interdisciplinary teams to bring them from pulp to prototype, and interdisciplinarity necessitates collaboration across various scales: laterally, where institutions collaborate with each other; internally, where departments within institutions collaborate on projects; and externally, where institutions break the canonical fourth wall and seek collaborations with their audience.

This case study will look at the current state of interactive documentary’s convergence with digital journalism and the role of collaborations in fostering convergence, as well as at collaborations that result from this convergence. For this case study, we looked closely at documentary projects from National Public Radio (NPR), Center for Investigative Reporting (CIR), ProPublica, Association of Independents in Radio (AIR), and WBEZ Chicago’s Curious City, all of which were made possible by different forms of collaboration. This section will contextualize and report on the views of the people who are leading new changes in the media landscape. By standing outside the institutional silos of both journalism and documentary, we hope to show why the convergence of these forms—and strategic collaborations between them—matter for the future of both disciplines at large.

“The border isn’t a line; it’s a place."1

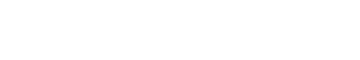

Such was the tagline for a 2014 interactive documentary project called Borderland. Led by NPR, the premise of the piece was to follow public radio host Steve Inskeep as he traveled along the U.S.-Mexico border and reported on what he found there (see Figure 1). With national tension building at that time around the immigration debate, Borderland endeavored to illustrate—in multimedia vignettes that included audio soundscapes, narration, photography, maps, and short videos—the U.S.-Mexico border as a vital place on which people depended to live and work (see Figure 2).

Figure 1. Screenshot of NPR’s “Borderland." Source: http://apps.npr.org/borderland/.

Figure 2. Introduction to NPR’s “Borderland." Source: http://apps.npr.org/borderland/.

The notion of borders was both the subject matter of Borderland and a convenient analogy for the inter-organizational collaboration that ultimately made the piece possible. While the concept of an interactive documentary told through different forms of media was not new in 2014, the production of Borderland involved new collaborations across institutions and generated new work flows between organizations and departments that did not previously exist.

The project was managed by the NPR Visuals Team, a recently-formed outfit in the newsroom that resulted from a merging of the former news applications team, which had served as NPR’s graphics and data desk, and the former multimedia team, which had created and edited pictures and video.2 The interdisciplinary visuals team worked to gather various types of media from the U.S.-Mexico border in near real-time. Radio host Inskeep and Kainaz Amaria, an NPR photographer, were on location recording audio and photos, while multimedia producer Claire O’Neill and interaction designer Wesley Lindamood were at NPR headquarters, in Washington, D.C., providing editorial feedback in near real-time about what material would make the final cut.

Both O’Neill and Lindamood needed to make quick decisions about what visual materials would best fit the audio story to be produced at the tail end of Inskeep’s trip. Additionally, O’Neill and Lindamood were on the lookout for visual materials that could be used for the Web version of the story. In the end, the audio stories were released first, on Morning Edition, one of NPR’s daily national news programs. The remaining media were then repackaged with the audio and released in an interactive documentary online that same month.

To help tell the story interactively, NPR and the San Francisco-based Center for Investigative Reporting (CIR) collaborated on how to publicize a data set about the location of the U.S.-Mexico border fence.3 As CIR’s senior news applications developer Michael Corey writes, CIR had filed several Freedom of Information Act requests with U.S. Customs and Border Protection and, “after several appeals, [CIR] received limited data showing where individual fence segments start and end." 4 But this was not the kind of detailed view that CIR needed for the joint story. CIR was told that more detailed data could potentially reveal sensitive information to drug cartels, illegal border crossers, or terrorists. However, Corey writes, this reasoning bothered him. After all, he asks, “How secret is a 10-foot-tall metal fence that runs along golf courses and through major cities?"5 To Corey, a drug cartel or terrorist trying to get into the U.S. would likely already know the “minutiae" about the wall’s locations, and releasing this information would not pose a significant risk.6

After being set back by U.S. Customs and Border Protection denials of CIR requests for complete data on the wall, Corey got creative. He realized that he could still cross-reference the data he was able to acquire, albeit incomplete, with satellite photography captured by Google Earth. After painstakingly discerning between canals, the fence, and other surrounding infrastructure from Google Earth photography, Corey used a mapping software called Java OpenStreetMap (JOSM) to trace the approximate location of the fence. The NPR Visuals Team then revised its interactive documentary to include the CIR-developed data set representing the approximate geographic location of the border fence. Thus, both organizations benefited from expertise that neither had on its own: CIR was able to find a publication venue for its data, and NPR’s Borderland was enriched by a data-oriented perspective on its story about the U.S.-Mexico border.

Throughout the NPR Visuals Team, Borderland is consistently cited as one of its most successful collaboration projects to date. When asked why the team might feel this way, team manager Brian Boyer responds, “I think part of it is related to priorities. The priorities were easy for Borderland because of the prominence of the project and the prominence of the people involved, with Steve [Inskeep] being a host and authority figure."7 Boyer explains that the clear lines of authority within the team structure made it easy to discern who was accountable for which task, a scenario that does not always play out this way with so many collaborators.8

Borderland’s success may also stem from the fact that collaborators within and outside of the institution were able to recognize and contribute their strengths. Boyer says, “[The visuals team is] good at making pictures, editing video, making charts and graphics … but we are not the subject matter experts."9 In other words, the visuals team focused on visual storytelling; radio host Steve Inskeep focused on the audio-based narrative and bringing ground truth from the field; and CIR contributed its border fence data set. These all culminated in a final, synthesized product.

These types of multi-faceted collaborations are not uncommon in today’s media landscape. Other news organizations that we approached also reported regular collaboration with outside organizations, with various motivations. Some collaborations result from mutual interest in a story; others happen to amplify audience reach; and still others occur for comparative advantage, enabling individuals or organizations to work with others that possess resources lacking in their own organizations.

For instance, because ProPublica is a news organization that is particularly adept at collecting and distributing data,10 it often ends up partnering with individual journalists, other news teams, or large news organizations in order to leverage its data sets and gain visibility as a news organization unto itself. ProPublica’s healthcare reporter Marshall Allen says that ProPublica partners with “over a hundred outlets," including NPR, Frontline, and CIR.11 Since ProPublica is a smaller news unit with about 40 people on staff, it makes sense to leverage relationships with other newsrooms to maximize audience reach, he says.12 NPR’s Brian Boyer adds that many of NPR’s stories are co-published on ProPublica’s online properties, which conversely allows other news organizations to amplify their audience reach as well.13

ProPublica is a news organization that has defined a niche for itself in the news ecosystem with regard to data gathering, analysis, and representation, and through collaborations with other news organizations, it is able to leverage its strengths, providing other news organizations with robust data sets to scaffold their storytelling and gaining a wider audience for itself in turn.

The Center for Investigative Reporting also leans on inter-organizational collaboration as a core part of its methodology. “CIR is highly collaborative at its core," says CIR Distribution and Engagement Manager Cole Goins.14 “We’ve partnered with media organizations on all platforms, in a variety of different ways, and have solicited insights and help from the public to inform and guide our reporting," he says.15 CIR’s most frequent radio collaboration is with KQED, a local public radio station in the San Francisco Bay Area. Both organizations have shared a reporter, Michael Montgomery, for the past few years, and KQED and CIR regularly co-produce stories and interviews for radio and the Web. CIR has also worked regularly with CNN, The Guardian (U.S.), and newspapers and TV stations across California.16

These collaborations generally range from publishing partnerships with slight edits for style and space, or they can be more collaborative in nature. Examples include CIR’s Hired Guns investigation17 with CNN and its Toxic Trails investigation with The Guardian (U.S.). For the former, both organizations did the reporting: CNN produced a video segment while CIR focused on the text stories and digital elements. For the latter, CIR did the reporting and writing while The Guardian (U.S.) team handled layout, design, and interactive elements that augmented the story. Both projects serve as examples of how different news organizations can collaborate in ways that play on each other’s strengths.

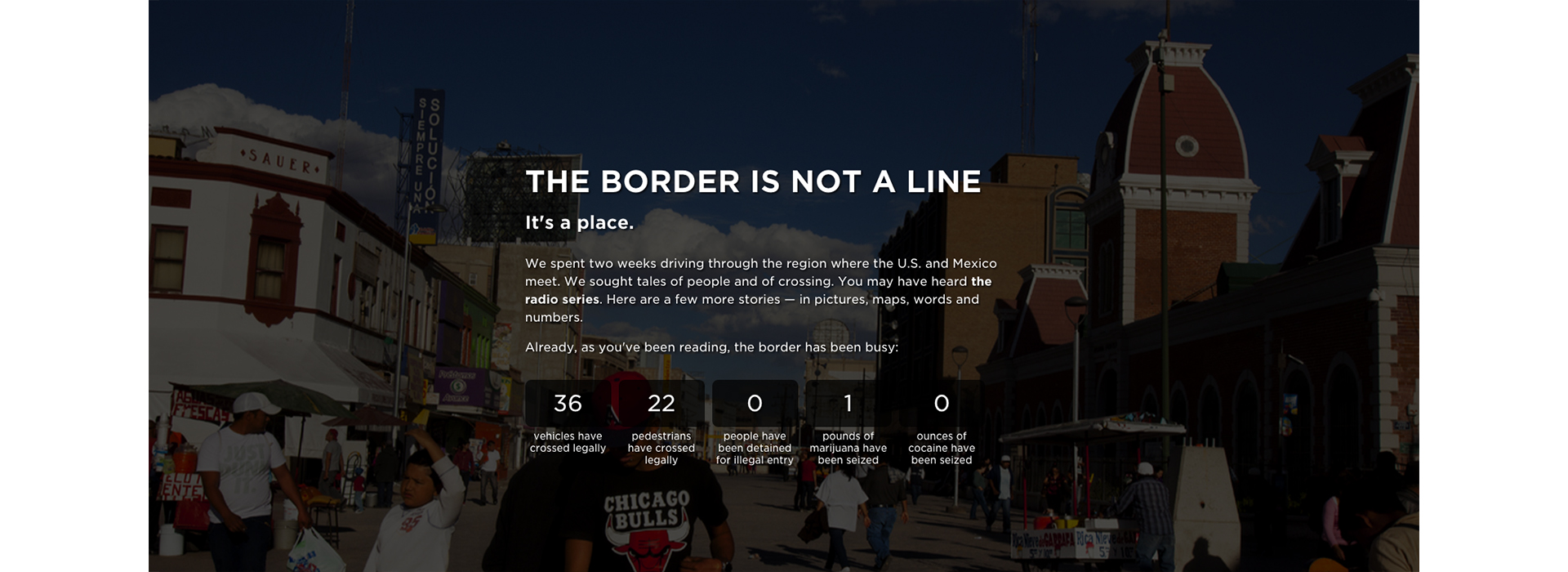

Another project, Rape in the Fields—an investigation into the sexual abuse of migrant women working in North America’s fields and packing plants—is a collaboration with CIR, Spanish-language broadcasting company Univision Documentales, PBS’s Frontline, and the Investigative Reporting Program at the University of California, Berkeley (see Figure 3). Since many of the affected migrant workers were Spanish-speaking women, CIR partnered with Univision Documentales in order to reach more Spanish‑speaking audiences, while Frontline and UC Berkeley aided with the investigative work. Goins says that the collaboration was worth it: “Such a hefty band of producers and publications helped facilitate substantial impact for the story that continues to resonate in California and across the country."18 Due to the project’s success, CIR is about to launch a companion to the original Rape in the Fields investigation, which was produced in collaboration with many of the same partners.

Figure 3. Screenshot of “Rape in the Fields" collaboration with Frontline, CIR, Univision Documentales, and the Investigative Reporting Program at the University of California, Berkeley. Source: http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/rape-in-the-fields/.

One way to mitigate the challenges of synchronizing with other collaborators presents itself in the form of CIR’s formal partnership with Public Radio Exchange (PRX), a content distributor with which CIR joined forces to distribute its investigative news public radio program Reveal. According to Goins, having a partner solely focused on distribution, and not tied to one particular story or project, ultimately helps CIR’s content reach more people.19 Traditional models of investigative reporting assume that the public will get information from a particular news outlet’s turf, whether from its homegrown print, websites, or channels. But Goins says that journalism can also be seen as a public service provided not just to the public, but also to other news organizations.20

Another core distribution strategy that CIR employs is helping other news organizations localize stories and data sets that CIR generates; this puts national or global stories into context for specific regional and local audiences and communities. For example, CIR’s coverage of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs hospital backlog was a national story that was then picked up by many local news outlets (see Figure 4). To achieve this, CIR worked on outreach with local news outlets to produce focused pieces based on the data. According to Goins, a key goal behind the outreach and focus on local news outlets was to drive impact: “The main goal for CIR is having an impact with our work, and our local partnerships are strategically geared to help build a drumbeat around issues that can highlight problems and potential solutions," Goins says.21

Figure 4. Screenshot of CIR’s “Reveal" podcast on VA hospital backlogs, a collaboration with Public Radio Exchange (PRX). Source: http://cironline.org/veterans.

Collaborations across institutions also build capacity in terms of developing new skills and work flows. The Association of Independents in Radio (AIR), a network of primarily independent journalists, is a nonprofit that, since 2010, has built a new research and development infrastructure within the public broadcasting system. Beginning in 2013, AIR’s Localore project matched independent film and radio producers with radio and television station partners to deploy a year-long storytelling project spanning multiple cities across the United States (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. Map of AIR’s “Localore" projects. Source: http://localore.net/.

In the first iteration of Localore, AIR hired ten lead producers based on their project pitches and matched them with stations across the U.S. that seemed to best fit those story pitches. The station partners provided significant support through the duration of the project. The idea was to enable stations to take on new, multi-platform storytelling initiatives while simultaneously providing producers with the support and resources to experiment with new storytelling forms.

For example, independent producer Delaney Hall pitched a project about local music cultures and was matched with KUT,22 Austin’s public radio station. The resulting project was the Austin Music Map,23 an interactive documentary of music and musicians in Austin, Texas. Hall and her collaborators also created MapJam, an ongoing community festival that brings the digital documentary platform to life on the streets of Austin. The festival now attracts thousands of citizens across the region and features local musicians who collaborate on the project. The project—and partner station KUT’s expansion of MapJam during three subsequent years—had an impact beyond its digital life, as evidenced by attendance at the music festival.

Another Localore project, Chicago-based WBEZ’s Curious City, led by then-independent producer Jennifer Brandel, challenged the way news organizations collaborated with audiences for story finding. WBEZ’s Curious City is a crowdsourced news platform that allows local Chicago public radio listeners to contribute to the editorial process of generating news stories. Through Curious City, WBEZ stories originate from public submissions of questions about things related to Chicago. WBEZ producers and editors sift through submissions and use a polling system to let other members of the public decide what they should investigate. Answering the submitted questions involves radio producers working with reporters, radio hosts, videographers, photographers, bloggers, comic artists, musicians, and anyone else in the community interested in helping out. “Curious citizens" who regularly submit questions are also invited to track down answers, some going as far as helping conduct interviews or supplying important documents for the final story.

Lead producer of Curious City, Jennifer Brandel, speaks about the philosophical implications of the collaboration model between journalists, institutions, and the public: “We viewed the journalist as a conduit between audience and interviewees… not [as a gatekeeper]. We broke down some of the institutional walls and allowed the public to influence editorial decisions and have agency."24 The logic behind this strategy is that the media content not only reflects the concerns of the local constituency, but is also co-authored by that constituency.

Getting Curious City off the ground was not without its challenges. As Brandel recalls, “The challenges were really about flying blind…. I knew what I wanted, but I didn’t know exactly what it would look like. I wanted to experiment to see if it worked."25 Fortunately, she had a supportive work environment at WBEZ that let her experiment. She was given freedom to try out new strategies, and there was no “naysayer" to stop her team from “doing things like taking a question and turning [it] into the story and having the product of that story be, for instance, an infographic about how poop gets processed in the city, printed on a roll of toilet paper."26 This kind of creativity was encouraged in these early days of development for Curious City; the point was to explore how local storytelling could be more participatory and more reflective of the voice of people living in Chicago.

For the Curious City project, WBEZ provided an editor who worked with Brandel, as well as interns who were able to help with production. These resources were available because AIR’s Localore was funding Brandel independently from WBEZ’s payroll. The idea of matching a producer with a station based on mutual interest—instead of financial viability—enabled a different type of relationship focused on content creation and capacity building at the station.

For Brandel, there was some initial concern about what risks this model posed to journalistic standards. For instance, what would it mean to base story pitches on audience questions? What if involving the public as interviewers made interviewees uncomfortable and hurt the scenario? What if the person was crazy? Brandel recalls “only great experiences," she says, and that people “really appreciated… the opportunity to see what reporting was like."27

One way that Curious City tested the waters at first was to see if the public would submit questions that would lead to interesting stories to investigate and tell. Brandel and her team posted a provocation on the WBEZ website: “What have you always wondered about Chicago and wish could be reported?" They immediately received responses containing topics and story ideas they found interesting. “Curiosity has a contagious quality to it," says Brandel.28 “Once a question is posed, you likely want to have closure. It’s a human force of nature and is undeniable," she adds.29 Brandel thinks this “can only be a good thing" for newsrooms, as it encourages newsrooms and the public to work collaboratively to find answers together.30 Still, she doesn’t believe in a free-for-all. Brandel’s team considered the ethical implications and possible risks of its work before pushing forward. In the end, Brandel says, it was a matter of trusting the process, her team, and the overall public that led to a positive experience producing the series.31

At the time of this writing, Brandel has taken the Curious City model to be incubated by Matter, a San Francisco-based media company incubator, with an additional round of $110,000 in funding from AIR’s New Enterprise Fund, meant to extend the capacity of particularly successful Localore projects (like Curious City) beyond those projects’ initial phases. Matter could potentially drive strategic changes for how Curious City’s model functions beyond newsrooms, Brandel says, and she is expanding her clientele to include “all content creators, for profit and nonprofit" alike.32 The next phase of the Curious City model will be about making tools for content creators to replicate aspects of what was done at WBEZ, according to Brandel.33

Meanwhile, back in Chicago, Curious City continues in its original form with many of the people who were on the flagship production team, including former interns who are now full‑time staffers. When asked what she has taken from her experience of running the pilot program in Chicago, Brandel responds:

I’m taking with me a firm belief that the public has valuable insights that can lead to original, useful, and popular stories for newsrooms. When I think about the holy grail for journalists, at the end of the day, the kind of story every newsroom wants to do is an original one—whether it’s illuminating a part of the past, highlighting something that is not often seen, or if it’s a hard-hitting investigation…. Something that is useful for the community. The story should also perform well. Not everyone is immune to the metrics dashboard…. There’s a lot of news, but not all of it is necessarily popular.34

Trying to represent the voice of the public is not a new concept, especially within public media, as the idea philosophically aligns with public media’s mission of representing public discourse. However, the combination of AIR’s independent support for Brandel as a producer, and Brandel’s particular model of letting the public influence editorial decisions directly for a digital storytelling initiative, did not exist before Localore.

“It’s very much to do with understanding the nature of the time that we’re in," says AIR Executive Producer Sue Schardt.35 That “demands extreme flexibility, extremely high appetite for risk. A fearlessness," she says.36 Schardt sees the Localore model as a way to build capacity for both stations and producers: while stations bring to the table advantages in “location, relationship, and legacy systems relative to the community," Schardt says, producers bring their fresh ideas, capacity, and AIR’s backing to get the job done.37

In terms of coordination, partnerships, and budget, Schardt says, “AIR was able, through its competition architecture, to create a relatively simple process for what would potentially be a time‑consuming, complicated negotiation."38 What did that process look like? Producers and stations both filled out different versions of the same form in order to document their storytelling interests. AIR connected the dots in terms of which producers might fit with which stations, and it encouraged them to reach out to each other without making anything official. Then, if the station and producer wanted to work together, they were asked to submit a joint proposal for AIR funding.

After the semi-finalists were chosen, AIR introduced Zeega, a potential digital partner with which station-producer pairs could collaborate. Zeega is a digital storytelling company that specializes in designing, developing, and producing interactive documentary projects.39 It was born of AIR’s first research and development initiative, called MQ2, and, according to Schardt, “shared the DNA of the producers that participated in Localore."40 Schardt says, “We told [station-producer partners] that we had a digital partner to make available to them who [could] help with the digital component of the project."41 If station-producer partners chose to work with Zeega, around $15,000 of their production budgets would be allocated to the company. Eight station-producer partnerships decided to hire Zeega, while others opted to hire their own design and development teams.42

Schardt sees AIR’s role in the Localore production process as one of “matchmaking, mediation, and managing a complex field of nearly 200 collaborating producers, a new type of role that is essential in a media landscape that increasingly fosters collaboration."43 Organizations that situate themselves outside of production and funding are few, but they play a unique role in synthesizing relationships that make collaboration possible. Individuals like Schardt can help secure funding from willing donors as well as connect people to each other, connect people to organizations, and connect organizations to organizations in order to make collaboration even more possible.

Motivations for crossing organizational borders through collaboration vary from one project to another, and they depend on each organization and project’s specific needs. Some collaborations form to share resources, as in NPR and CIR’s story on U.S.-Mexico border relations. Others, like AIR’s Localore, seek collaborations in order to build capacity in organizations or to localize content. Other collaborations form in order to reach wider, engaged audiences. Whatever the motivation, the result of collaboration is an exchange of information and resources that enhances the skills and knowledge of institutions, allowing them to apply their new resources to future products or projects that they might not have accomplished alone.

While finding ways to collaborate with audiences outside the newsroom is one tactic that newsrooms are exploring, some newsrooms seek to make collaboration within the newsroom more effective as well, which is what this report will explore next.

Serendipity Day

At NPR, based in Washington, D.C., there is something called Serendipity Day. Every fiscal quarter, NPR designates three days during which employees across all departments are encouraged to pitch mini-projects to work on together. Employees can self-organize and engage to the extent of simply sharing knowledge, or they can actually work on a project together. This is how multimedia producer Claire O’Neill and senior interaction designer Wesley Lindamood ended up working on Lost and Found—an interactive documentary that tells the story of 1930s‑era photographer and hobbyist Charles W. Cushman, whose body of work was discovered recently, by accident. The piece combines audio narration, images, and a time‑based slideshow built on Popcorn.js, a JavaScript framework that allows for integration of media for interactive storytelling. In 2013, the interactive documentary won first place in the Feature Story, Innovation, and Best in Show categories in the competition from the White House News Photographers Association (WHNPA),44 as well as other honors.

But before they won any awards together, O’Neill and Lindamood were working for two separate NPR departments: the multimedia team (responsible for editing pictures and video) and the digital media design team, respectively. Today, the two teams have merged into the NPR Visuals Team, which manages multimedia production for both short-form and long-form storytelling, often experimenting with interactive documentary (see previous discussion of Borderland).

The merging of these teams occurred in 2013, with the departure of senior multimedia producer Keith Jenkins and the stepping-in of his replacement, Brian Boyer, previously NPR’s news apps managing editor. The merger was further catalyzed by a project called Planet Money Makes a T-Shirt, an interactive documentary produced for NPR’s Planet Money, a national show about business and finance. The documentary—about the entire pipeline of creating a t-shirt from the cotton farm, to the factory, to the customer—was a Web-based documentary that included videos, audio, photos, and a customized, navigable experience for the audience on the Web (see Figure 6).

Figure 6. Screenshot of “Planet Money Makes a T-Shirt." Source: http://apps.npr.org/tshirt/.

Both the news applications team and multimedia team spent eight weeks producing the project. Whereas members of both teams previously tended to sit in separate areas of the NPR office, the project required them to seek out a shared workspace in order to make decisions and sketch out ideas. Kainaz Amaria, who was a photographer on the T-shirt project, recalls being able to overhear conversations that she usually would not have heard about Web editing, visual edits, Web optimization, and “the more technical things that we were less familiar with," she says.45 Being in closer contact with other team members also lent itself to more discussion, more in-person troubleshooting, and more exposure to unfamiliar disciplines. Thus, instead of a situation in which specialists were working with other specialists in the same discipline (for example, photographers with photographers), the proximity forced team members to become comfortable working together with individuals from different disciplinary backgrounds.46

Interaction designer Lindamood recalls that there was also a risk of being “overambitious" while working with such an interdisciplinary team.47 In retrospect, he says that the team was careful not to add too many design features to the final product for Planet Money Makes a T-Shirt. From the beginning, in fact, the team focused on not letting technology get in the way of the story.48

The tension between designing for interaction and designing for optimal storytelling is widely discussed among members of the NPR Visuals Team, and it is a topic that defines the visuals team culture. As team manager Boyer explains, “Just because a story is ‘important’… doesn’t mean it needs a bespoke visual component. That is the wrong reason to choose to do a visual project. The right reason to choose to do a visual project is [that the] story demands it: I have no better way to tell it with just words or just video."49 The balance between maximizing both interaction and storytelling is a delicate one, and there is no standard answer for what is best; for the visuals team, it depends on what the story itself demands. However, the T-shirt project helped the visuals team confront these questions together, as a collaborative unit, and to articulate the philosophy behind design decisions.

The interactive documentary about the supply chain of t-shirt production also outlined new workflows for story production across departments at NPR. Various members of the NPR Visuals Team consider T-Shirt a seminal project that established an ideal workflow for their group. For example, the habit of sharing a workspace during the T-Shirt project literally forced these teams to work more closely together and more collaboratively, a precursor to the merging of the teams under Boyer’s direction.

To this day, when the visuals team hires new people, Boyer looks for “collaborative generalists"; in other words, people who do not necessarily specialize in one particular field, like photography or programming, but instead have a broad set of skills across disciplines and are comfortable working with others who are similarly generalists.50 Boyer’s reasoning is so his team can think about projects from different perspectives and be able to solve problems collectively.51

For example, each Thursday, the team holds a meeting called “Look at This," during which visuals team members collectively curate and critique Web-based news projects of interest. Projects chosen for critique can be from NPR, but many of them are from other news organizations or other storytelling platforms to which visuals team members want to bring attention. This weekly exercise exposes the team to the work of others outside of their institution, and in providing constructive critiques of the works presented, the team members are able to better understand what they do—and do not—want to accomplish for their own agenda.

The visuals team agenda is mostly driven by priorities set in the newsroom, but some team members are assigned to longer-form projects and “slow news" stories that are more evergreen and less time sensitive, Boyer says.52 Because same-day news stories have tight deadlines, the interactive documentary form—which takes longer to produce—is almost never used for breaking news.

In addition to building new tools and platforms for stories, the NPR Visuals Team is cognizant of how to share and transfer knowledge about these tools and platforms both internally and externally. The visuals team blog highlights current strategies, projects, and outcomes for anyone, either in-house or in the general public, who might be interested in looking at how projects are built or in replicating the project framework with different content. Team members also use open-source code templates on GitHub,53 a repository for code templates that is open for users both inside and outside of NPR. Interaction designer Lindamood says, “Making components reusable enforces the discipline of documentation and sharing."54

This culture of sharing contributes to knowledge construction for the interactive documentary form; it also enables practitioners inside and outside of NPR to engage with different interactive documentary tools and practices. Thus, the merging of both the multimedia and news applications teams into one entity is perhaps telling of the changes that newsrooms must face with emerging storytelling platforms and methods.

Going outside

Often, the stories that resonate with audiences are those that make them feel as if they were there. Storytellers seek to bring a sense of there-ness to their work, whether by evoking a sense of place, by building empathy for and connection with a subject, or by actually traveling to a community to hear directly from its members. Whereas traditional journalism and storytelling forms reached audiences asynchronously, after the fact, it is now possible for audiences to react to stories in real time and for journalists and storytellers to respond. In some cases, as with WBEZ’s Curious City project, audiences may even be part of the research and story discovery process.

ProPublica, an independent, New York-based, non-profit newsroom that produces investigative journalism in the public interest, has also worked to include audience input in its reporting. Paul Steiger, the former managing editor of The Wall Street Journal, founded the organization in 2007. It is now run by Stephen Engelberg, a former managing editor of The Oregonian and investigative editor of The New York Times, as well as by Richard Tofel, former assistant publisher of The Wall Street Journal.

ProPublica healthcare reporters Marshall Allen and Olga Pierce, along with Tom Jennings and Ocupop’s Michael Nieling, collaborated on an interactive documentary about risks for patients in the healthcare system called Hazardous Hospitals, which was put together in four days in 2013 and covered issues of quality of hospital care and patient harm (see Figure 7). While Jennings produced the piece, Allen and Pierce mostly helped provide the content and research for the story. According to Allen, Jennings based the interactive documentary on similar ones he had done for Frontline. The story is told through video interviews, GIFs, text, questionnaires, and social media. All of these forms invite the audience to engage with the medium, the story, or ProPublica staff in some way.

Figure 7. Screenshot of “Hazardous Hospitals." Source: http://projects.propublica.org/graphics/slideshows/hazardous_hospitals

The nature of Allen’s work focuses on reporting on the status of healthcare quality, ranging from hospital inspections to surgical mistakes, as well as engaging ProPublica’s audience around healthcare issues by facilitating discussions on ProPublica’s patient harm community Facebook group. The group, which has about 2,500 members, is open, so all posts are publicly accessible to non-members as well. Journalists and patients regularly interact with each other in the group to discuss issues of patient care, which sometimes even generates story leads, Allen says.55 ProPublica has also designed a patient harm questionnaire, which has been answered by 800 people thus far. There is a separate questionnaire for healthcare providers.56 The forms export responses (about 30 data points) to a spreadsheet, and responses are then analyzed.

These forms of engagement are based on an opt-in model, where users volunteer their information and their time to participate; Allen moderates the discussions and reports that results have been positive for the team overall.57 With the patient harm Facebook group, ProPublica has been able to gather “way more information than [it needs] for any stories [it is] going to do," Allen says, and the group is ultimately able to bring issues of concern to an audience that [is] responsive to its content.58 ProPublica has also used this crowdsourced, participatory methodology to gain insight from the public on stories about segregation, student loans, foreclosures, and other topics.

AIR’s Localore project also took an approach of going straight to communities and audiences to help tell a story. The main theme of Localore was “Go Outside." Collaborating producers were encouraged to immerse themselves in local communities to study and inform their experiments, as opposed to staying in the newsroom. For Localore’s next round of local productions, launching in 2015, “reposed" is the operative word, says executive producer Sue Schardt.59 “We’ll want producers, as a first step, to get a lawn chair, set it up on a corner in the local community, study, and listen to what goes on. Only then can you begin to build."60

Similarly, stations are expected to host events that bring listeners from their broadcast community together rather than relying on reaching listeners through purely digital and technological means. Producers in the upcoming round will rely on existing technology versus investing heavily in new, immersive documentary platforms, as in previous rounds. Schardt explains: “We’ll want to understand what technology citizens in the neighborhood are already relying on. It may be smoke signals. It’s got to be guided by what is meaningful in the community’s lives."61

This flexibility expresses itself in the apparatus that Localore producers have used to collect stories. For example, producer Anayansi Diaz-Cortes’ Sonic Trace project, for public radio station KCRW in Santa Monica, California, involved inviting Oaxacan immigrants in Los Angeles, California, to record their interviews in a portable storytelling booth nicknamed “La Burbuja" (“the bubble" in Spanish). Erica Mu’s Hear Here project, for KALW in San Francisco, California, convened communities at pop-up events that featured local artists, storytellers, and musicians at local libraries. The aforementioned Curious City project at WBEZ Chicago created various ways for residents of Chicago to submit questions about Chicago online, in person, on air, and at events, which producers would then go out to investigate for their stories.

This method of bottom-up story making requires new ways of thinking about, defining, and recording metrics for success and impact. AIR created a methodology for gathering data across more than sixty digital, broadcast, and street-level (i.e. live event) platforms. Stations and producers were required to fill out a form to the best of their ability once a month for twelve months. Every station incubator had assigned an “impact liaison," who was tasked with completing monthly surveys about station metrics and engagement.62 During the year after Localore productions wrapped up, AIR aggregated the collected data in a comprehensive “What’s Outside?" report,63 which was distributed to all the producers and station partners as well as across other organizations seeking to learn more about this model.

CIR’s investigation into California’s strawberry farms and the use of pesticides in and around them, which was released in 2015, also included going directly to communities of concern. Not only did the story involve reporting on the current use of pesticides at strawberry farms in Oxnard, California, but CIR also chose to reach out directly to community members to raise awareness about pesticide risks. The team started by looking up a database of addresses associated with Oxnard’s zip code, then they cross-checked those that were located closest to pesticide hot spots. They mailed out almost 4,700 postcards containing information about their story as well as a number that people could text to find out how many pounds of pesticides had been applied near their home address.64 This was an explicit experiment in reaching people through direct mail; CIR’s metric of success was the number of people who texted the number, but unfortunately, only around 25 to 30 people responded. Despite the paucity of responses to the postcards, CIR’s main goal in using direct mail to reach its audience was to seek a more analog means of distributing crucial information related to its investigation.

The case points to a key tension that CIR faces in trying to further engage its audience with crucial content: that of digital vs. analog. Distribution and engagement manager Cole Goins reflects on CIR’s attempt to merge the digital and analog in order to get information directly to audiences: “Digital doesn’t live in a vacuum. Everything digital is tied to the physical…, the real world, and tied to real people."65

After the initial pesticide investigation came out, another key CIR collaboration developed involving the Tides Theater Company, based in San Francisco. The company is CIR’s partner on a larger project called StoryWorks, an ongoing collaboration to translate investigative journalism into theater productions. Goins and Jenna Welch, of Tides, set up workshops between the theater company and students from Rio Grande High School, in Oxnard, to develop and perform five‑minute plays about their experience living and going to school next to an area at risk of pesticide oversaturation. One of the plays was performed with CIR’s full StoryWorks production, Alicia’s Miracle, which was then brought to Oxnard in February of the same year. The play is a response to CIR’s reporting from the community it intended to reach: “These are the people that are literally most affected…This is the target community," Goins says.66 In a sense, CIR’s methodology deliberately disrupts the traditional transmission model of journalism and instead privileges aspects of community organizing and capacity-building to reach its constituency directly. It is less focused on directing traffic to a print or digital story, and more intent on facilitating change in the real world, Goins says.67

Today’s technology enables storytellers to connect with audiences through digital platforms. This breaking of the fourth wall has given storytellers license to experiment with new forms of audience engagement. Stories have the ability to become immersive experiences that offer producers and the public the ability to go there, to where the action is and where people are most affected.

Conclusion

The organizations we investigated in this case study represent only a small sample of the current media landscape, but conversations with those who have been part of collaborative interactive documentary projects within newsrooms reveal a multitude of reasons why collaborations form across, within, and outside of institutions. Collaboration is both a method and mode of operation: a way of pooling resources for a common project, and at the same time a more common occurrence among organizations in today’s digital media space.

Some open questions remain about the convergence of interactive documentary and journalism. Do these new and more frequent collaborations generate a completely new form of storytelling? When asked whether the work they do falls more into one bucket or another, NPR’s Lindamood responded, “The stuff we do is always journalism.… There’s no such thing as objective journalism. Deciding something is newsworthy is a subjective choice already."68

CIR suggests that it does not necessarily matter how the work is classified; rather, the form is led by what producers believe is best for the audience they are trying to reach. One must be “very open to these creative modes of storytelling, not necessarily even coming from you but maybe facilitated by you," CIR’s Goins says.69 He adds that it is “a shift in [media] culture … a desire to incorporate and interact with the public more regularly, openly, and meaningfully through journalism."70

Marshall Allen at ProPublica says, “I don’t think the form dictates whether it’s journalism or not."71 To him, the work done at ProPublica is inherently journalistic, with some projects told more creatively and others in a more straightforward fashion.72

Given these responses, there appears to be a slight disconnect between how players in this space are seen and how they see themselves and their roles. From one angle, the increasing use of digital formats for storytelling could be read as an adaptation of forms, an effort to keep up with the changing landscape. From another, it could be read as a deliberate attempt to reach constituencies more instantaneously on digital platforms—which are now more pervasive than ever before—and to offer new modes of engagement between auteurs and audiences.

Far from being a quarantined lab for technological specialists, the digital era welcomes producers who are interdisciplinary generalists. Audiences, too, have an opportunity to become involved with the media production cycle, and news organizations increasingly anchor their work in soliciting and facilitating audience responses. Collaboration is a priority rather than an afterthought, from research and development phases all the way to project launch. Though our research does not claim to have the answers about what the future of collaboration in this field will look like, it seems quite certain that media organizations will step into it together.

1. “Borderland" (2014) [http://apps.npr.org/borderland/]. ↩

2. “How We Work | NPR Visuals" (2015) [Blog.apps.npr.org]. ↩

3. Michael Corey, “The surprising tools CIR used to map the U.S.-Mexico border fence," The Center for Investigative Reporting, 10 April 2014 [http://cironline.org/blog/post/surprising-tools-cir-used-map-us-mexico-border-fence-6255]. ↩

4. Ibid. ↩

5. Ibid. ↩

6. Ibid. ↩

7. Phone interview with Brian Boyer, Cambridge, MA, 31 May 2015. ↩

8. Ibid. ↩

9. Ibid. ↩

10. “About ProPublica" (2015) [https://www.propublica.org/about/]. ↩

11. Phone interview with Marshall Allen, Cambridge, MA, 15 December 2014. ↩

12. Ibid. ↩

13. Boyer, 31 May 2015. ↩

14. Interview with Cole Goins, Emeryville, CA, 31 December 2014. ↩

15. Ibid. ↩

16. Ibid. ↩

17. “Hired Guns" (2015) [http://cironline.org/hiredguns]. ↩

18. Goins, 31 December 2014. ↩

19. Ibid. ↩

20. Ibid. ↩

21. Ibid. ↩

22. “KUT Austin" (2015) [http://kut.org]. ↩

23. “Austin Music Map" (2014) [http://austinmusicmap.com/]. ↩

24. Phone interview with Jennifer Brandel, Cambridge, MA, 31 May 2015. ↩

25. Ibid. ↩

26. Ibid. ↩

27. Ibid. ↩

28. Ibid. ↩

29. Ibid. ↩

30. Ibid. ↩

31. Ibid. ↩

32. Ibid. ↩

33. Ibid. ↩

34. Ibid. ↩

35. Interview with Sue Schardt, Dorchester, MA, 11 March 2015. ↩

36. Ibid. ↩

37. Ibid. ↩

38. Ibid. ↩

39. “Zeega" (2014) [http://zeega.com]. ↩

40. Schardt, 11 March 2015. ↩

41. Ibid. ↩

42. Ibid. ↩

43. Ibid. ↩

44. “2013 Eye of History: News Media Contest," The White House News Photographers Association (WHNPA) [http://www.whnpa.org/contests/multimedia-contest/2013-eyes-of-history-new-media-contest/]. ↩

45. Interview with Kainaz Amaria, Washington, DC, 26 February 2015. ↩

46. Ibid. ↩

47. Interview with Wesley Lindamood, Washington, DC, 26 February 2015. ↩

48. “How and Why Cross Disciplinary Collaboration Rocks," Open News, 2 January 2014 [https://source.opennews.org/en-US/learning/how-and-why-cross-disciplinary-collaboration-rocks/]. ↩

49. Boyer, 31 May 2015. ↩

50. Ibid. ↩

51. Ibid. ↩

52. Ibid. ↩

53. “NPR Apps GitHub" (2015) [https://github.com/nprapps]. ↩

54. Lindamood, 26 February 2015. ↩

55. Allen, 15 December 2014. ↩

56. Marshall Allen and Olga Pierce, “Providers: Tell Us What You Know About Patient Safety," 18 September 2012 [http://www.propublica.org/getinvolved/item/providers-tell-us-what-you-know-about-patient-safety]. ↩

57. Allen, 15 December 2014. ↩

58. Ibid. ↩

59. Schardt, 11 March 2015. ↩

60. Ibid. ↩

61. Ibid. ↩

62. Ibid. ↩

63. “What’s Outside?" (2014) [http://www.airmedia.org/PDFs/Public_Media_2014_Final_Interactive.pdf]. ↩

64. Interview with Cole Goins and Ariane Wu, Emeryville, CA, 11 February 2015. ↩

65. Goins, 31 December 2014. ↩

66. Ibid. ↩

67. Ibid. ↩

68. Lindamood, 26 February 2015. ↩

69. Goins, 31 December 2014. ↩

70. Ibid. ↩

71. Allen, 15 December 2014. ↩

72. Ibid. ↩