27 May Moments of convergence and innovation between documentary film and interactive media, Part 3

The Research Forum is OpenDocLab’s space for researchers to voice their opinions and test new theories. As part of our mission to promote the exchange of ideas about the new arts of documentary, we hope to encourage academic discussion and debate about these emerging forms by creating a place where researchers can develop ideas and interact with the field. The views presented here belong to their authors and will necessarily take different forms. In the spirit of the documentaries we study, we look forward to community collaboration and exchange as the ideas explored in the Research Forum take root, grow, and support the development of the field.

Moments of convergence and innovation between documentary film and interactive media: The eighteenth and nineteenth centuries

by Arnau Gifreu Castells

To formulate a relevant concept for the interactive documentary field we need to explore some aspects of the two key areas: the documentary genre and the interactive medium. This new series presents a combined, parallel, and comparative historical chronology of these areas up to the present moment of confluence. The two stories we are following here begin, to a certain extent, in the seventeenth century. It should be noted, however, that a number of theorists, scientists, inventors, and entrepreneurs had already developed a handful of theories and experiments that led up to what happened a few centuries later. We will focus our analysis on the seventeenth to the nineteenth century and place special emphasis on the twentieth and early twenty-first century. In this post we will address some points of convergence and innovation that occurred in the nineteenth century.

The nineteenth century is notable for the great progress made in the two areas studied. Starting from the seventeenth century, it is as if every century, except for the eighteenth century, has been affected by a gradual crescendo that has brought us to the present moment of fusion and convergence in the two fields.

During the nineteenth century, era of great change and invention, the idea of creating moving images was a mystery that was beginning to be investigated. A series of investigations and experiments made film a reality. A number of theorists, scientists, artists, and people associated with show business turned entrepreneurship theories into real applications. The nineteenth century can still be considered very important with respect to inventions that made the birth of the interactive nonfiction genre possible.

Figure 1. Difference Engine

Source: Wikipedia:

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/8/8b/Babbage_Difference_Engine.jpg

The first and especially the second decade of the nineteenth century shows several interesting and important parallels in the development of the two fields. On one hand, in 1822 Charles Babbage presented his project for the Difference Engine, and later on, in 1830, the basis for computing in the Analytical Engine.

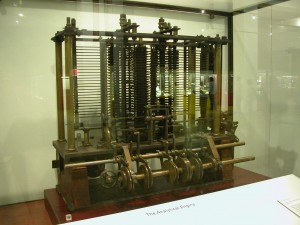

Figure 2. Analytical Engine

Source: Wikipedia:

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/a/ac/AnalyticalMachine_Babbage_London.jpg

During this time interval (1820-1830) Peter Mark Roget surprised the scientific world with a science communication to the Royal Society of London on the topic of the “Persistence of vision” (1824), which was published the following year under the name “Explanation of an optical deception in the appearance of the spokes of a wheel seen through a vertical aperture” (Roget, 1825, Royal Society of London). It can be seen that in a period of two years two English geniuses introduced two research projects that would become crucial for the development of both the documentary and digital media.

Figure 3. Peter Mark Roget

Source: Wikipedia:

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/9/96/Roget_P_M.jpg

Also noteworthy is the temporal proximity between the proposals of the German scientist Herman Hollerith (a pioneer in the development of computer and automated processing of large volumes of information) who built the Tabulating Machine in 1885, and related experiments in the generation of moving pictures in the last quarter of the nineteenth century, direct precursors of Edison’s Kinetoscope and the Lumière brothers’ cinematograph.

Figure 4. Tabulating Machine

Source: Wikipedia:

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/4/4e/HollerithMachine.CHM.jpg

If we look at and analyze the time interval, we can see how interactive documentary is a derivative of Hollerith’s and Louis Lumière’s inventions. The interactive documentary uses the Internet as a broadcasting medium and to automatically process large volumes of information (content).

Moreover, film in its first formulation was purely documentary: the “actualités” or “filmed news” were filmed records of some specific events in a specific time and space. There were no script or actors and it was natural in appearance. To sum up, the device allowed the Lumière brothers to record live events, capturing reality in motion, and Hollerith’s work allows us to browse Internet content, not only as textual unconnected fragments, but motion picture documentaries and other media (multimedia, hypermedia, and transmedia). All this in twenty years since it first began.

Arnau Gifreu Castells (PhD)

Research Affiliate, MIT Open Documentary Lab

agifreu@mit.edu

References

Gifreu, A. (2012), The interactive documentary as a new audiovisual genre. Study of the emergence of the new genre, approach to its definition and taxonomy proposal and a model of analysis for the purposes of evaluation, design and production. [Doctoral Thesis]. Barcelona: Universitat Pompeu Fabra. Communication Department.

Gifreu, A. (2013), Pioneros de la tecnología digital. Ideas visionarias del mundo tecnológico actual. Barcelona: Tic Cero. Editorial UOC.

Jones, S. (2003), Encyclopedia Of New Media: An Essential Reference to Communication and Technology, New York: The Moschovitis Group.

Lee, J.A.N. (1995), Computer Pioneers. Los Alamitos, California: IEEE Computer Science Press.

Norman, J. M. (2005), From Gutenberg to the Internet: a Sourcebook on the History of Information Technology. Vol. 2, Novato California: History of Science.

Roget, P. M. (1825), “Explanation of an optical deception in the appearance of the spokes of a wheel seen through a vertical aperture.“ In Nichol, W. (1825), Philosophical Transaction of the Royal Society of London, part 1, pp. 131.

Valladares, Y. (2010), Ciencia y Autores en el desarrollo del Cine y la Imagen. Madrid: CR Servicios Gráficos.

Wikipedia. Difference engine: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Difference_engine

Wikipedia. Analytical engine: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Analytical_Engine

Wikipedia. Persistence of Vision: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Persistence_of_vision

Wikipedia. Tabulating Machine: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tabulating_machine

List of quoted experiments/innovations

Difference Engine

A Difference Engine is an automatic mechanical calculator designed to tabulate polynomial functions. The name derives from the method of divided differences, a way to interpolate or tabulate functions by using a small set of polynomial coefficients. Both logarithmic and trigonometric functions, functions commonly used by both navigators and scientists, can be approximated by polynomials, so a difference engine can compute many useful sets of numbers.

Analytical Engine

The Analytical Engine was a proposed mechanical general-purpose computer designed by English mathematician Charles Babbage. It was first described in 1837 as the successor to Babbage’s Difference Engine, a design for a mechanical computer. The Analytical Engine incorporated an arithmetic logic unit, control flow in the form of conditional branching and loops, and integrated memory, making it the first design for a general-purpose computer that could be described in modern terms as Turing-complete. Babbage was never able to complete construction of any of his machines due to conflicts with his chief engineer and inadequate funding. It was not until the 1940s that the first general-purpose computers were actually built.

Persistence of vision

Persistence of vision is the phenomenon of the eye by which an afterimage is thought to persist for approximately one twenty-fifth of a second on the retina (Roget, 1824; Plateau, 1829) and believed to be explanation for motion perception; however, it only explains why the black spaces that come between each “real” movie frame are not perceived. The true reason for motion perception is the phi phenomenon.

The theory of persistence of vision is the belief that human perception of motion (brain centered) is the result of persistence of vision (eye centered). The theory was disproved in 1912 by Wertheimer but persists in many citations in many classic and modern film-theory texts. A more plausible theory to explain motion perception (at least on a descriptive level) are two distinct perceptual illusions: phi phenomenon and beta movement.

Tabulating Machine

The tabulating machine was an electromechanical machine designed to assist in summarizing information and, later, accounting. Invented by Herman Hollerith, the machine was developed to help process data for the 1890 U.S. Census. It spawned a class of machines, known as unit record equipment, and the data processing industry.

The Cinematograph

A cinematograph is a motion picture film camera, which also serves as a film projector and developer. It was invented in the 1890s. There is much dispute as to the identity of its inventor. The device was first invented and patented as “Cinématographe Léon Bouly” by French inventor Léon Bouly on February 12, 1892. Leon Bouly coined the term “cinematograph,” which translates in Greek to “writing in movement.” It is said that, due to a lack of fee, Bouly was not able to pay the rent for his patent the following year, and Auguste and Louis Lumière’s engineers bought the license.

Further readings

Research Forum | Arnau Gifreu Castells on Documentaries and Digital Media, Part 1

Research Forum | Arnau Gifreu Castells on Documentaries and Digital Media, Part 2

Research Forum | Arnau Gifreu Castells on Documentaries and Digital Media, Part 3

Research Forum | Arnau Gifreu Castells on Documentaries and Digital Media, Part 4

Research Forum | Arnau Gifreu Castells on Documentaries and Digital Media, Part 5

Interactivity technologies, key factor for the interactive documentary (i-docs)

The evolution of the Internet, key factor for the interactive documentary (i-docs)

The evolution of the Internet, key factor for the interactive documentary (II) (i-docs)