29 Jan How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love ‘The World Brain’

The OpenDocLab teamed up with Indiewire and the Sundance Institute to publish a series of articles about the 2013 Sundance New Frontier festival, written by OpenDocLab research assistants. This was previously published in Indiewire’s Criticwire blog, and is reposted with permission.

How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love ‘The World Brain’

Julie Fischer

I walked into Ben Lewis’ much-buzzed documentary “Google and the World Brain” ready to root out its transmedia strategy. How were the creators of a film about freedom of information going to make the film’s message accessible to the widest possible audience? How would the producers turn their content loose on the web to sound the alarm about information ownership and lend their voice to the call for openness? In my rush to assess the new media element, I’d totally missed the point.

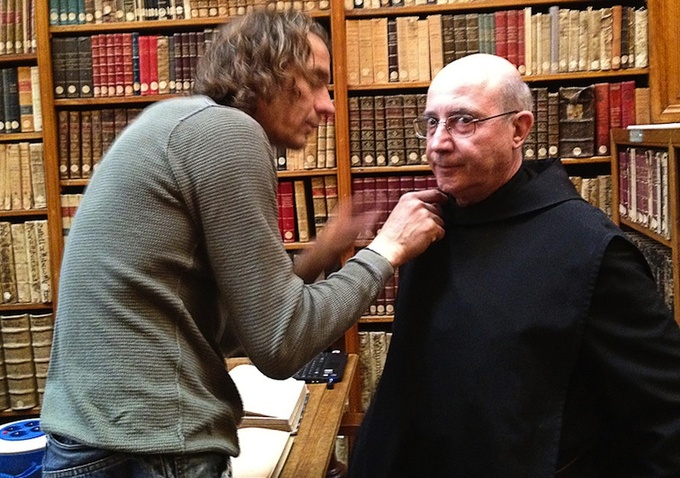

“Google and the World Brain” takes as its narrative backbone the rise, fall, and continued forward motion of the Google Book project, originally code-named “Project Ocean” presumably because, as one of the film’s erudite interviewees points out in an enjoyably blunt moment, it was big. Filmmaker Ben Lewis traces the mounting copyright conflict between Google and authors, publishers, and librarians that led to lawsuits in 2005, a settlement in 2008, and the 2009 Department of Justice hearings that ultimately overturned that settlement. Google is still scanning books through individual agreements with publishers, but it is no longer able to scan copyrighted works en masse.

The film is a cautionary tale about the power and perils of information ownership. The “World Brain” of the title is a phrase coined by science fiction writer H.G. Wells to describe the ability of all human knowledge to be collected together and made accessible to everyone. The film points out that this idea — the vision of a universal open-access library — is a dream almost as old as humankind itself.

But the film also points out what those who followed the Google Books legal battle already know: if that knowledge is centralized under one point of control, it is only as good as that holder’s intentions. Google has the financial power and global reach to create something like a universal library, but the fact remains, as Lewis’ interviewees point out from many perspectives, it is not a library. Each book it makes available is a book that it holds power over, giving Google the ability to censor, destroy, or charge for information. Coursing beneath this film’s pulsating score and futuristic visualizations is a Big Brother nightmare scenario.

But this is not truly where this film wants to go; or, at least, it’s not the only place. “Google and the World Brain” takes a more complex and well-reasoned look at the Internet landscape. The message of this beautifully crafted film is that the Internet is exactly half of what you think it is. It is not utopian or dystopian, but it is certainly not going anywhere any time soon. Scrutinizing the legal precedents and the public and private debates about Internet culture is key if we want to shape a positive future.

This is a particularly resonant topic at Sundance. The Internet impacts more than just books; it shapes every concept of copyright and artistic ownership — not to mention artistic authorship — across the board. That includes documentaries like Lewis’ film, along with a new and exciting set of Internet hybrids. And there is a small but vocal debate being held about these works’ value, and their future.

Web-native interactive documentaries are coming into their own. Two of the best-known projects were featured at Sundance through support from the festival’s New Frontier section: the moving and brilliantly participatory “18 Days in Egypt” in 2011, and the imaginative, engaging interactive nature saga “Bear 71” in 2012. These works are dramatically engrossing in two very different ways. The burgeoning web documentary scene is quickly discovering a myriad more ways to work the web into creative, immersive storytelling experiences.

But there is a reason that the highest praise many of these works receive is to be called “cinematic.” While some interactive storytelling works soar to new and unexpected reaches of immersion and impact, others fall flat. There is craftsmanship in synthesizing information and emotional expression — be it a book, a film, or an interactive web-based experience. “A book is not an extra-long Tweet,” says “Google and the World Brain” interviewee Jaron Lanier, getting a laugh.

And he’s right. Having spent much of my time at Sundance in the New Frontier venue, I’ve been immersed in some of the best exhibits of multimedia storytelling today. New Frontier is one of the leaders in supporting the mastery of this medium and shepherding web-native artists out from under the masses of web content, the everyday, throwaway comments and video clips and photos, the content that is important because it’s honest or funny or strange, but that isn’t quite art.

What “Google and the World Brain” has to say to these new works is twofold. First, it is a reminder to the small minority who are totally immersed in web-native cinematic storytelling that a film about technology need not be plugged into it. “Google and the World Brain” is a masterful documentary. It will undoubtedly have an effect on anyone who sees it, and people will see it, whether there is a massive transmedia strategy or not. As it proceeded in its look at the world of the web, it also became increasingly satisfying to watch this film in a theater and to know that there was nothing behind the curtain and no wires connected to the screen.

This film gently, quietly makes me aware that for every purely creative transmedia experience, there is an engrossing transmedia ad campaign that is tracking what you buy. For every captivating location-based story-world created with Smartphones and apps, there is a trail of location data that can be used or abused.

Ben Lewis’s film tells us not to panic, just to remain aware. After all, as “Google and the World Brain” says definitively, knowledge is power. In a small way, this film takes on the roll of Big Brother in the best sense of the phrase. It is telling its younger siblings, these new, wild, web-reliant media experiences, to remember that theirs is a medium of powers and of pitfalls. Please proceed, but with caution.

Julie Fischer is a first year graduate student in MIT’s Comparative Media Studies program. She is a research assistant for the Open Documentary Lab.