13 Jul Conversation Starters

Share your story.

These days, I see those words everywhere. On news websites. Digital archives. Interactive documentaries.

It’s a deceptively simple request. Although “share your story” seems like an easy ask, in practice it can be anything but.

First off, many people don’t share. Web usability consultant Jakob Nielsen has posited a 90-9-1 rule of online participation. Ninety percent of web visitors “lurk,” simply consuming content, while 10% contribute occasionally. Only one percent of users are “heavy contributors,” and they generate the majority of content on participatory sites.

In general, research supports Nielsen’s guideline. Scholars differ on the exact breakdown (70-20-10 has been suggested instead of 90-9-1), but most agree that only a fraction of a website’s visitors make the leap from consumption to participation.

Where does this leave “share your story” platforms? How can creators encourage participation?

In May, I had the pleasure of seeing Zeega‘s Jesse Shapins speak at Toronto’s HotDocs conference. Participation, Shapins argued, must be authored. In other words, content creators have a responsibility to make story sharing easy for audiences.

Shapins suggested that creators should make simple, targeted asks of visitors. Instead of asking for stories, ask for photographs. While working on the collaborative project Mapping Main Street, Shapins and co-creator Kara Oehler asked site visitors to contribute photos of their town’s Main Street. Photographs were an easy, specific thing for people to contribute.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZrHVPmk7vls[/youtube]

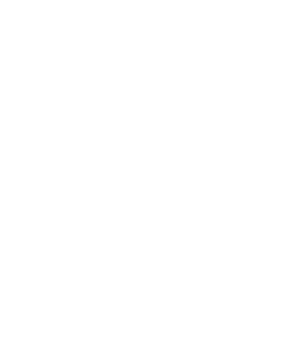

While working at the 9/11 Museum, I helped moderate the online archive Make History, designed by multimedia firm Local Projects. We asked people to “add their story” of 9/11 or the aftermath to the Make History archive.

Visitors could submit video, images, or text-based “stories.” Very few people sent written stories. By far, the majority of submissions were photos. In many cases, however, the photos served as a gateway to narrative. People would upload pictures, and write about their experiences in the caption. On Make History, the photographs served as prompts, or conversation starters.

Make History led me to believe that participation works best within guidelines. Successful story-sharing platforms set constraints. In some senses, restaurant review site Yelp can be seen as one of the most effective participatory “storytelling” platforms around. To borrow Shapins’s turn of phrase, Yelp’s participation is authored: the purpose of Yelp stories are clear – they’re reviews of local businesses. People know why they’re contributing, and what kind of information the site’s audience wants to read. Yelp’s constraints help focus its content, and lower the barrier to entry.

The Johnny Cash Project, a much lauded participatory storytelling project, is also built on constraints. Users pick a frame of Cash’s “Ain’t No Grave” video, and recreate it. The submissions can take any approach, but they must replicate the original video, and they must be in black and white. These rules give the project aesthetic and visual cohesion, and they make it easier for people to contribute.

[vimeo]http://vimeo.com/15416762[/vimeo]

Constraints help people participate. It’s a cliche that the blank page is hardest part of writing, but when it comes to web based projects, the truism rings true. People need a prompt to spark their story, and a context in which to place it.

Over the past few weeks, I’ve been watching a collaborative storytelling project unfold. It has all the flavors of high drama– part train wreck, part tragedy– and it’s being written by thousands of people, in various corners of the Internet.

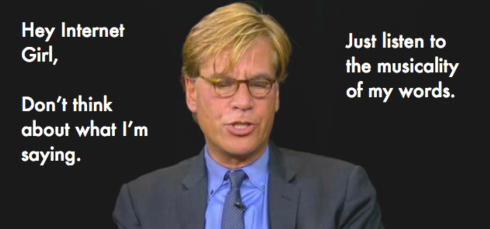

A few weeks ago, Aaron Sorkin self-destructed on the junket for his new HBO show The Newsroom. Condescending to Toronto Globe and Mail reporter Sarah Nicole Prickett as “Internet Girl,” Sorkin instructed her to “write something nice.” Prickett struck back with a bruising portrait of Sorkin.

“I’m sick of girls who don’t know how to high-five,” he says. He makes me try to do it “properly,” six times. He also makes me laugh; I’m nervous, and it’s so absurd. He loves it. He says, “Let me manhandle you.” Then he ambles off, hoping I’ll write something nice, as though he has never known how the news works, how many stories can be true.

Prickett’s piece spread across the Internet, sparking memes, blogs, opinion pieces, and YouTube videos. Kevin Porter’s “supercut” of Sorkinisms, released June 25th, has gotten more than 550,000 views on YouTube– 300,000 more than the pilot episode of The Newsroom.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S78RzZr3IwI[/youtube]

Is the Internet backlash against Aaron Sorkin “participatory” storytelling? It isn’t “story” in the Hollywood 3-act model, or even a walk-and-talk, but it’s certainly narrative. People are weaving stories together, and riffing off each other. The “stories” differ in tone– from impassioned anger to poking fun, but they share a central character– Sorkin– and, critically, a catalyst– the Globe and Mail interview. Without Prickett’s piece, the Sorkin stories wouldn’t exist. The interview was kindling. A conversation starter. People are expressing themselves in response. There’s a source text, or rather, a source provocation.

To share stories, we need prompts. These prompts could be authored (“submit your photos of Main Street”) or ripped from the headlines (“hey, Internet Girl”), but when we’re creating projects that rest on audience participation, they can’t be forgotten. Sharing stories is easiest when people have something to react to. To get users to respond, participatory story projects must prompt conversation. Storytelling is hard, but it’s even harder in a vacuum.

Prompts aren’t new. Where else does the term “conversation starter” come from? But online conversations show us their value. Sorkin’s interview is far from the only storytelling starter. Within a few days of Kony 2012’s release, people were remixing it and responding–telling their own version of the story.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c7jzwn45–Y[/youtube]

Fans have been remaking fictional narratives for decades. Last week, Elisa Kreisinger wrote an impassioned defense of her Mad Men remix videos, which have gotten more views than AMC’s official previews.

For Lionsgate & AMC, [remix videos] are great way for their content to reach a younger demographic… re-interpreting branded content for a millennial audience is a part of my generation’s remix culture.

[vimeo]http://vimeo.com/38741664[/vimeo]

Stories spark stories. The Sorkin, Kony, and fan remixes are prompted, created in conversation with other narratives. In a recent blog, independent film producer Ted Hope argued that the media industry should move towards

embracing both a business model and community focus on an ongoing conversation between the story world initiators and those that engage with it.

As usual, Hope is right on the money. Stories spark conversation, and these conversations can evolve into their own narratives. If we think of stories as conversation starters, where does that get us? What can we learn from the Internet girls?

Katie Edgerton/MIT