11 Mar Virtual Scrapbooks

I’m lucky enough to be taking William Uricchio’s Documentary Techniques and Technologies class here at MIT. It’s a seminar that touches on film history, but also looks forward to new forms of documentary. Narrative has come up time and again in class. How do web documentaries tell stories? How do those stories build on, and depart from, traditional film narrative?

New media docs sometimes get branded as the “future” of documentary. However, I’d argue that Internet-based documentaries aren’t the heirs to theatrical docs as much as they’re a related, but distinct, art form. For me, a key differentiator is this issue of narrative. If you hold up “filmic” storytelling as a model for web docs, it can be like trying to fit a square peg in a round hole.

Why? Different mediums are good for different types of stories. Films, for example, tell streamlined narratives well. In the Hollywood context, this is often plays out as a character learning, or failing to learn, a particular lesson. Television dramas, by contrast, are long form. Because of the length of the serial story (going on for months, or even years), they can become a vehicle for exploring characters or issues over time, with more vacillations and sidetracks than allowed by 90-minute films.

The web is both a distribution channel and a storytelling medium. Entertainment content is increasingly platform agnostic, meaning I can download Jack White’s new album while streaming Breaking Bad—I don’t have to go to the record store or even subscribe to cable. As a distribution channel, the web allows me to self-curate and get content more-or-less instantaneously.

The web as a storytelling medium is something completely different. There’s a tendency in some circles (we can be particularly guilty here at MIT) to see the web as an ultimate fulfillment of human technological achievement, the kind of medium into which all others flow, but that overlooks the Internet’s technological specificity.

What does the web do well? It can handle big data sets. It can make it easy for lots of people, in dispersed locations, to interact with each other. It allows for immediate distribution, dissemination, as well as real-time posting and access. Collaborative contribution can happen in a snap.

Do those features support documentary storytelling in the way we’re used to it? Not really. The web is a great distribution channel for linear documentary films, but if a 90-minute feature was created for the web, I’d argue that it wasn’t really taking advantage of the potentials of its medium—and is in fact, actively working against it. After all, who stays on a single webpage for 90 minutes?

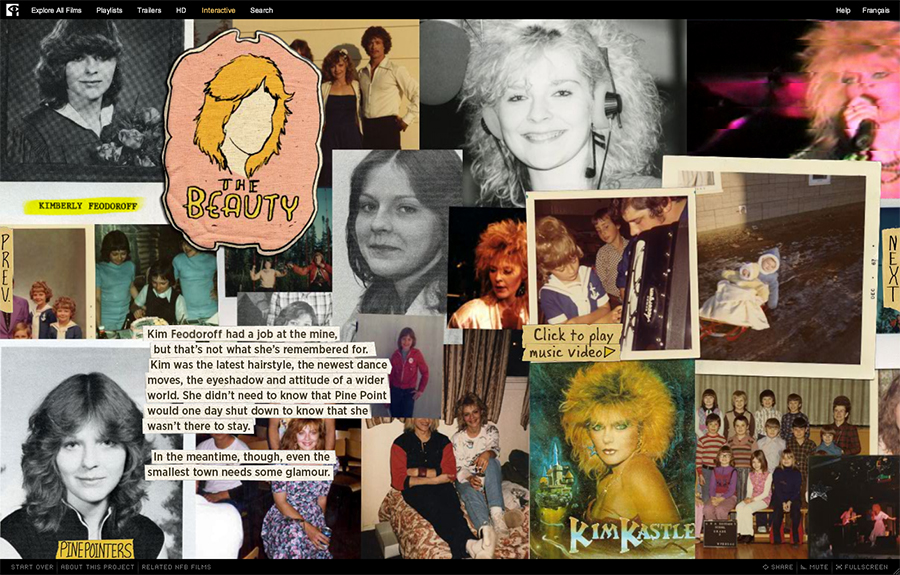

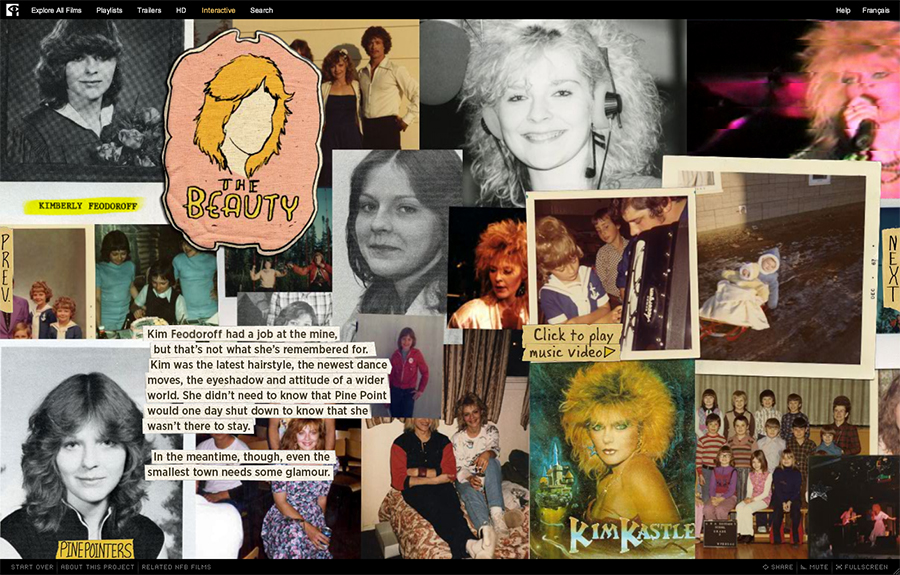

Welcome to Pine Point (NFB) is an engaging web doc in the virtual scrapbook model.

What kind of stories work best for web documentaries? Mysteries and game-like problem solving narratives seem like no-brainers, taking advantage of computer interactivity. Scrapbook-like projects, aggregating different forms of media and user contributions also seem to be a natural fit. Online media can be bite-sized. In museums, we had a rule of thumb: people wouldn’t stand and watch a video for more than two minutes, and even that was pushing it. The web might not be that cut and run (after all, you’re probably watching a web doc while sitting down)—but when we use the Internet we’re trained to move and browse.

I think that web docs aren’t so much films as we’re used to thinking of them, as virtual scrapbooks. Internet nonfiction storytelling builds on the lessons of traditional documentary, but it’s a different animal all together.

Katie Edgerton/MIT