05 Jun Puppet. Snake. Mask. Devil. Robot. LA DIABLITA ROBOT at Co-Creation Studio

by Kat Cizek

CAMBRIDGE Mass., May 29 — A women-led Quechuan team from Bolivia brought their Neo-Andean Devil story robot to MIT last week.

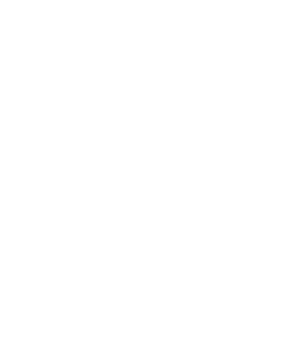

Storyteller Violeta Ayala and roboticist Camila Claros, supported by engineer Paulo Sanjines Arnez, workshopped their animatronics puppet with scholars, technologists and artists, hosted by Co-Creation Studio at the MIT Open Documentary Lab (ODL). The devil-robot will have the ability to interact with audiences and its surroundings through artificial vision and natural language processing. It draws on Bolivian and Quechuan mythology, mask-making, and the traditional dance La Diablada from the Bolivian carnaval. The robot is part of their larger VR and Immersive installation, PRISON X, aimed to exhibit at major film festivals, museums and galleries around the world.

Roboticist and programmer Camila Claro assembles the Diablita Robot prototype.

The team brought a small hand-sized physical prototype, as well as a full-scale La Diablada dance mask that was unboxed from a massive wooden crate at every meeting.

“We will give her a wicked, naughty and mischievous personality in keeping with the myth of the Neo-Andean devil just as in Prison X, she will antagonize the audience” says the team. The team will create a 3D model of the skeleton of the robot and the mask in order to 3D print all its parts and pieces, using Andean colors, crafts and designs of our millennial ancestral culture fused with cutting edge multi-materials in 3D printing technology. The dress of La Diablita will be designed by Maria Corvera Vargas, a Berlin-based Bolivian fashion designer and pioneer in up-cycling; and it will be hand made by Bolivian artisans. The installation will be co-created using the Quipus as a starting point.

The physical robot will invite audiences to learn to dance prior to entering the VR storyworld, which mixes social reality and mythology of Bolivian prison cultures.

Violeta Ayala describes the workshop:

“My time at the Co-Creation Studio at MIT has been truly transformative. It opened up a world of possibilities in the relationship between technology and storytelling, and made me wonder how these developments will shape our stories, ethics and feelings.

Surrounded by technology I was reminded of the Quipus and their relationship with masks, the patterns of Andean fabrics, and the weaving that exists in our Bolivian pop culture as a very direct line of connection between our past, present and future. The innovations being made at the Co-Creation Studio lead me to reflect upon the way our ancestors shared our history with us despite colonization, the way our thinking has changed through time, and how it is evolving still. Today you can even see the Chinese influence in modern devil masks in Bolivia because we are experiencing a neo-colonization from China. We are also influenced by the US with the homogenization of their coca-cola culture, ironically coca leaves come from the Andes.

Human creativity is limitless, however context is everything. I am open to experimentation but I must trust my instincts and look internally for inspiration. We live on many levels, our lives and experiences are not horizontal or linear but they exist in many directions and shapes and have many layers. In the end everything is about our personal story, which builds our community story together and through time a culture is built.

As a Quechua, my chain has been damaged, through colonization, the genocide of my people and the physical destruction of my culture. My first and foremost role as storyteller is to pick up the pieces and re-imagine my story. Stories define us and make us unique and because of that difference we connect with each other as humans.

The idea that “we are all equal” comes from a colonial and patriarchal perspective of domination. The dominant culture masquerades their advantage behind the romanticism of equality. This perceived equality denies our potential to be different and creates a sense of superiority for the dominant culture. It creates the “helping” syndrome of the white man, while taking away their responsibility of self-reflection and the possibility of an honest interaction between the dominant and the colonized.

We the colonized, tend to equate our differences with weakness, and weakness leads to a feeling of inferiority. We are constantly chasing a culture that does not belong to us. It feels like the dominant culture says “come, we are all equal” and it does not matter how fast we run, we always end up on the last rung of a ladder, looking up to their created world.

The complexity of our stories cannot be viewed as a linear form of narrative which follows a beginning, middle and end, this is a neo colonial tool used to make us believe we are all equal and to codify our stories. Theatre, Dance, Film, VR, AR, AI, Robotics and other emerging mediums of communication are the tools to tell our stories in all their multiplicity and complexity, we must use their power as a tool for decolonization. Technology is good as long as we control it but the moment that tech becomes our puppeteer we are lost. The devil is in the detail.

The pattern of a Quipu -•—•-•—-•— can be likened to the pattern of a machine, we understood the language of computing as a tool before the computer was even imagined. Weaving can be found in all the cultures in the world and it developed simultaneously in different ways. I am looking to the strength of my ancestors in passing our stories to me and the evolution of our thought process. My culture is not lost, my culture is not broken, my culture has been damaged but my culture is evolving. We are Neo-Andean.

It is time to see the strength of difference, the strength of our diverse cultures, and invite the possibility of a conversation eye-to-eye. A complex conversation which encourages difference. It could be humanity’s chance to use technology and storytelling to build a future for all.”

Unboxing a Diablada mask from 2019 made in Washington DC.

While at MIT, the team met with artists, technologists and scholars, in a custom-designed series of meetings and talks to incubate the story and UX of the devil-robot. Professor William Uricchio kicked off the sessions with a keynote on the cultural role of robots, illustrated with historical images of robots in science, cinema, theatre and literature. “Human tend to create beings in their own likeness. They defer to the robot those attributes that are our own,” he said, pointing to, amongst many other examples, the 1920 silent film The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, the story of the Jewish Golem in Prague, Karel Čapek’s 1921 theatre piece Robot, and the Terracotta soldiers of Qin Shi Huang, the first Emperor of China.

Professor Uricchio presented robots through cultural history including The Cabinet of Dr Caligari (1920 Silent German horror film), Karel Capek’s Robot (theatrical premier in 1921), the Jewish Golem, and the Terracotta Army (buried with the first Chinese Emperor in 210-209 BCE).

Professor Uricchio presented robots through cultural history including The Cabinet of Dr Caligari (1920 Silent German horror film), Karel Capek’s Robot (theatrical premier in 1921), the Jewish Golem, and the Terracotta Army (buried with the first Chinese Emperor in 210-209 BCE).

At the Personal Robotics Lab, PhD students Sam Spaulding and Randi Williams described the pipeline of robot creation, from character development in animation software to building physical robots. “Making robots is a team sport,” said Spaulding. Randi Williams described the lab’s research into human-robot and AI interaction at Boston-based children hospitals, where they noted sharp differences between children and parents’ relationships to the characters on different platforms. They compared interactions with the same characters on-screen versus puppeteered by humans and completely automated physical robots. They discovered that the fully automated robots tended to elicit the most emotional and social responses. The screen-based characters elicited passive interactions of the child to a screen, leaving the parents/guardians at a distance. The puppeteer-controlled characters created a theatre-like environment with minimal interactions, while the fully automated robots created much more engaging social and emotional interactions. The case for the personal and social robots was made convincingly.

La Diablita robot team meets PhD students Sam Spaulding and Randi WIlliams at the Personal Robotics Lab.

La Diablita robot prototype meets Huggable robot at the Personal Robotics Lab.

Randi Williams of the Personal Robots Lab describes character development from animation to robot.

La Diablita Robot workshop at Biomechatronics Lab.

Kathy Bisbee, Open Doc Lab fellow, explained her experiences with community-based VR labs. The ensuing discussion revolved around the risks and profound responsibilities of bringing technologies (and the corporations who own them) into communities beyond the digital divide.

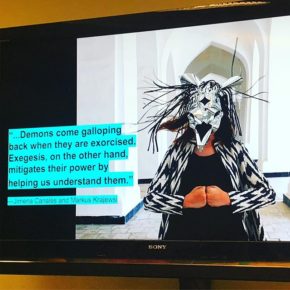

Marisa Jahn’s presentation on Daemons.

Sandra Rodriguez describes all that happens outside of the frame, the VR headset and in this illustrated case, the physical Panorama Rotunda of 1802. In this immersive experience, users were primed to perceive an exaggerated sense of height through a trick of building excessive staircases, and blackened hallways to isolate users from outside world.

Left to Right: Paulo Sanjines Arnez, Violeta Ayala, Claudia Claro, Nexi the Robot, Katerina Cizek, Lara Baladi, William Uricchio and Claudia Romano.

At the MIT Museum, the team caught on display historic robots from the MIT collection, and discovered innovative knot mechanisms for precision control.

Artists Lara Baladi and Marisa Jahn each showcased their work with masks, participatory design, archives and the historical record.

Meanwhile, government surveillance of Indigenous Mapuche communities in Chile was the focus of grad student and Open Doc Lab Researcher Josefina Buschmann’s talk to the team, which gave the group deeper insight into how the colonization of Indigenous land is increasingly articulated through technologies in the air, using drones, satellites and invisible infrastructures.

Sandra Rodriguez, artist and scholar, gave a custom-built talk on immersive experiences beyond the VR headset, providing examples and specific ideas for the team’s project. She was overflowing with ideas and questions that resonated with the team: “What happens when the puppets become puppeteers? What happens when we dance with the devil?”

Finally, the team shared lunch with the Center for Civic Media, facilitated by Research Assistant Samuel Mendez, where colleagues gave insights into their own experiences with computer vision, natural language processing and cultural computational models specific to communities.

The Prison X / La Diablita Robot workshop was generously supported by Cara Mertes at JustFilms of Ford Foundation, from an idea hatched during the Prison X mainstage pitch at IDFA Forum 2018, thanks to Caspar Sonnen and Yorinde Segal. Co-Creation Studio and MIT Open Documentary Lab are both supported by Lauren Pabst at the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation.

The workshop was produced by Claudia Romano, designed and facilitated by Katerina Cizek, and curated by Katerina Cizek, Sarah Wolozin, Samuel Mendez and William Uricchio.

PRISON X VR project is supported by Create NSW, Tribeca and Sundance Talent Forum (and was part of the CPH:DOX Lab led by Mark Atkin). La Diablita Robot is funded by United Notions Film LLC (US), Immigrant Media Pty Ltd (Australia)and Fat VR (Chile).