03 Jun Liveblog: Theo Rigby on the Making of Immigrant Nation

Filmmaker and photographer recently visited OpenDocLab shortly after the NYC launch of his interactive, participatory documentary Immigrant Nation. The following is a live blog of his presentation, including some documents related to the project’s design and development process.

Filmmaker and photographer recently visited OpenDocLab shortly after the NYC launch of his interactive, participatory documentary Immigrant Nation. The following is a live blog of his presentation, including some documents related to the project’s design and development process.

Theo Rigby: I’m a filmmaker from San Francisco. I’ve been working with immigrant and undocumented communities for 10 years.

Tonight I wanted to share the story of the story behind Immigrant Nation and how I’ve gotten here over the past 10 years. With interactive, participatory storytelling projects, there’s no roadmap. It’s not a traditional, feature length documentary film.

We are a nation built by immigrants, a country dependent on immigrants. This is a shared history that we all have – but don’t often talk about. It affects the languages we speak, how we look, but famillies don’t sit down and talk about shared histories and heritage. Because of this, our shared history dissipates.

When I throw out this question: “What’s your immigrant story?”, people have a lot to say. Often there’s quite a bit they don’t know.

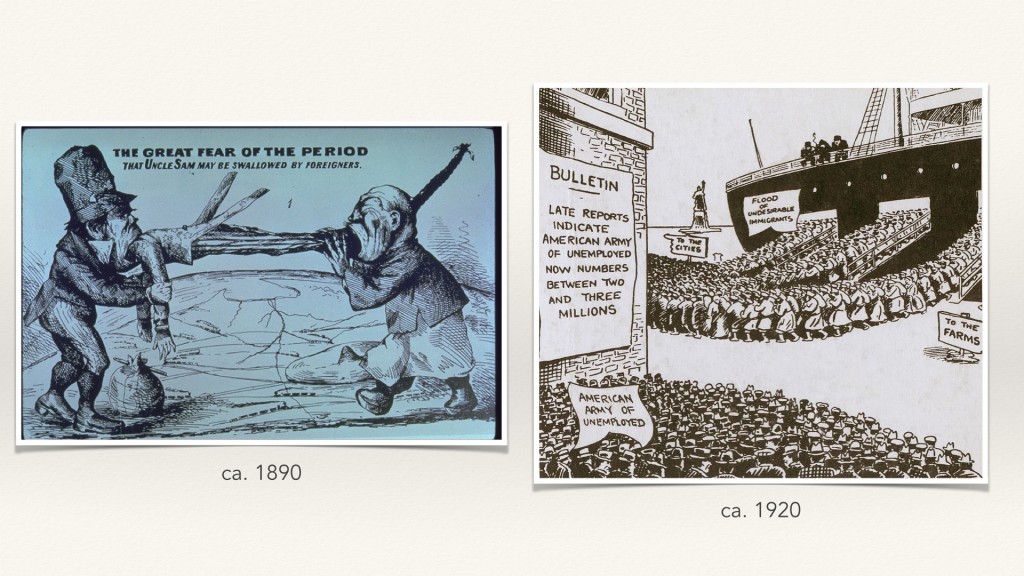

For hundreds of years there has been discrimination against immigrant groups.

This is strikingly similar to conversation that’s happening around immigration today. News coverage doesn’t offer complexity and depth in the immigrant story.

What does “Immigrant” mean to us?

Why is the story so skewed and oversimplified?

I went to the border, to experience it myself and talk to people. I was a photojournalist at that time, not yet making films. I went to the US / Mexico border and started asking questions, snooping around.

I connected with a mixed status family, a mom with 14 kids – and became immersed in their lives. What does it mean to live in a place where border police drive by every day, and if they asked for your papers, you’d be deported?

Lucila is a mother. She walked over the border with seven of her children. Marisol was picked up by the border patrol a year after I began photographing them.

I got a call at 9am in California, their sister telling me, they got caught. She wasnt even saying “help me,” she was saying, “What do we do? How do we grasp this situation?” At that point your role as a filmmaker, as journalist, as advocate, as friend gets thrown up in the air.

I ended up helping them find a lawyer to take on their case pro bono. Border control wouldn’t tell the sister where her family was. Then I followed the immigrant justice system for the next three years. It’s complicated, everyone agrees the ‘system is broken’. This brought all of these issues very much home for me, and made it personal.

I returned to San Francisco and began a program for undocumented youth to tell their own stories. We gave them cameras and matched them with photo mentors.

When I went to grad school, these issues were still very important to me. I decided to make my thesis film about a family being separated by deportation.

Sin Pais

SIN PAÍS (Without Country) from Theo Rigby on Vimeo.

The power of the traditional (short) film

Last week I had a screening, and this was made in 2010. Four years later, people are still emailing me and calling me. This still resonates, because its obviously still a huge issue.

This is really the story of two people and the ripple effects on the community and on their family. It’s getting the concept of a mixed status family out there. We may know what that is here, but many people don’t. Usually the younger kids are born in the US, older kids and parents are undocumented or of various legal statuses. 9 months after they were deported, immigration officials let the parents come back on a temporary visa.

How to get different pieces of media out there in different ways?

– Sin Pais was seen by immigration officials deciding Mejia case

– 30+ Film Festival screenings

– National POV broadcast

– PBS created educator’s guide

– Educational distribution to 400 schools

– Countless community screenings to this day

We got to see how this kind of media – straightforward and standard documentary media – how it works in the world and how it resonates.

The family screened it on the big screen for their family and friends, we watched the film on PBS on TV live.

After all this I feel like there’s a bigger story out there. I’m missing a lot of pieces. How can I create a project that is much much more inclusive, and constructed in less of a traditional way?

Thinking about my great grandmother, who came here from Latvia in 1903. There was a debate in the family about why. Maybe she fell in love with the wrong person. She met Mikel from Odessa or St. Petersburg. They were farming to survive. A hundred years later, the older sister in the Mejia family is a farmer here, in Arizona, working in a hydroponic tomato farm. There’s an innate connection – we’re all connected.

How can an interactive project get at these connections?

iNation: The Beginning

In the beginning I had:

-no team

-no content

-no coding / developer skills

-no roadmap

-no money

-no web-native storytelling experience

Trying to fundamentally shift the perception of immigrants after hundreds of years of discrimination and infinite obstacles.

The Competition: videos of babies and dogs, that get millions of views; while serious things get many fewer views.

So we made a film, because that’s what we knew how to do. We know how to tell stories in that way. Short films were going to be a part of the bigger project, so we tried to focus on the issues in immigration crossing many boundaries – trying to make a film that’s not only an immigration film.

The Caretaker

The Caretaker: an iNation short film from Theo Rigby on Vimeo.

Distribution from the beginning:

– Started partnership with National Domestic Workers Alliance (NDWA)

– Opportunities to start film festival screenings

– NYT Op-docs webcast places iNation on the map

– National Broadcast on PBS program ‘Local, USA’

– NDWA incorporates film and platofrm into their work

– Webcast on POV next week

We couldn’t have picked a better film to start with, because it connects with so many people on so many levels. For example, I was about to do a live TV broadcast and the broadcaster leans over to me and says “a Fijian man took care of my dad in the last 2 weeks of his life, and that man means more to me than anyone in this world.” Then the broadcast start.

I had multiple interactions like that. THIS started a relationship wtih the National Domestic Workers Alliance. This gave us opportunities to start screening, showing in traditional ways. NDWA is going to be incorporating the film into their work with affiliates across the country. One in the Bay Area has latched on to it and used it in their ESL classes as a storytelling tool.

The Online Platform

We got a grant from the Tribeca Film Institute.

Developers are not cheap, especially the really good ones. We’re really lucky to get funding. Next steps, we had to research what is out there. At the time, we couldn’t just go to Docubase to see so many transmedia and interactive projects in one place. We had to piece together inspiration — what’s out there that we want to do? We found user-generated content interesting from here, an interesting data viz from here…

We needed to find a design dev team, and I don’t speak the language. If you’re sending out an RFP to design teams, don’t call it an RFP – it’s a “vision statement.”

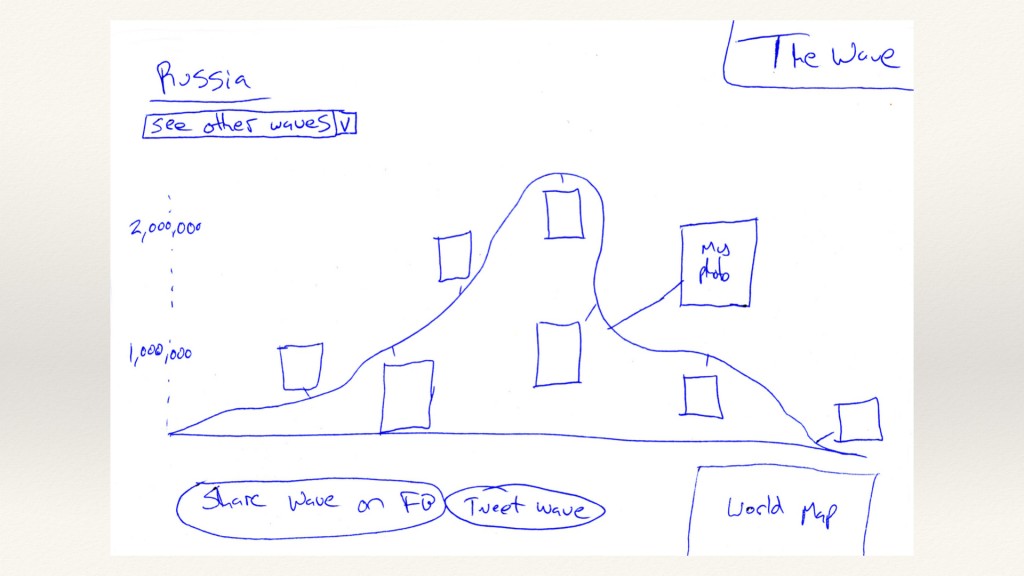

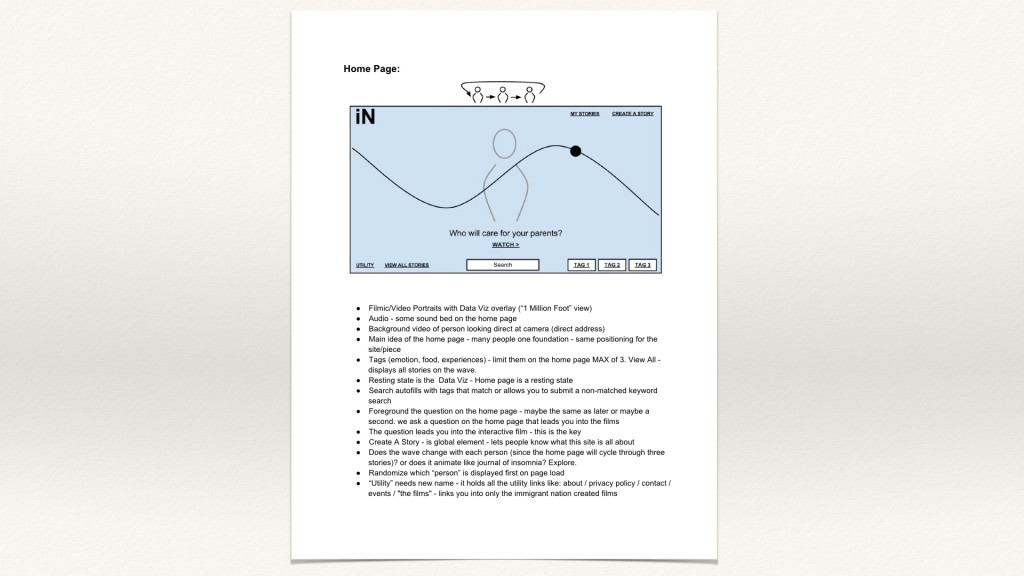

One of the biggest challenges: How do we create some kind of visual representation of what we’re thinking? We started by creating something really simple: a graphic designer creating Photoshop documents, then animating with AfterEffects.

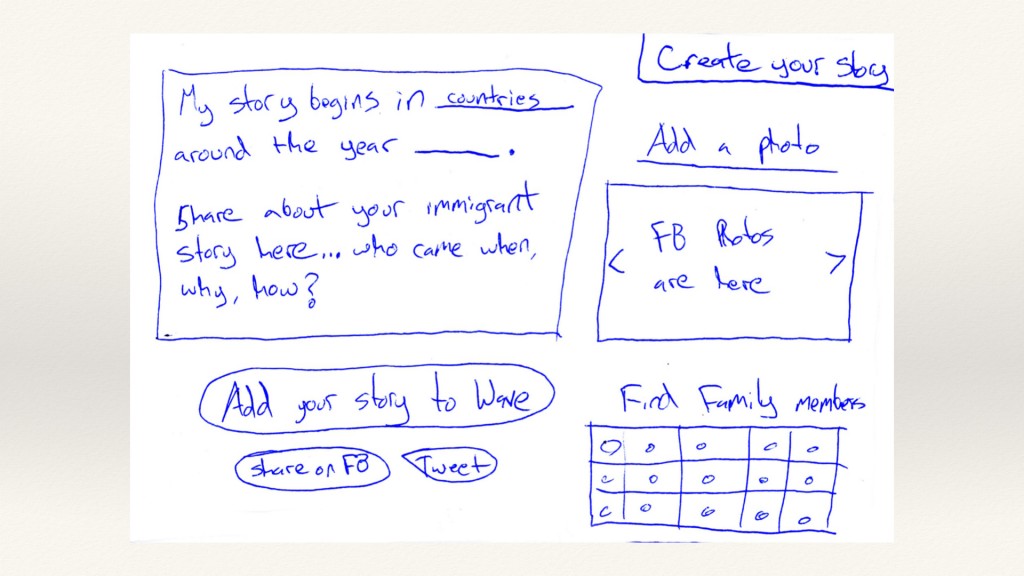

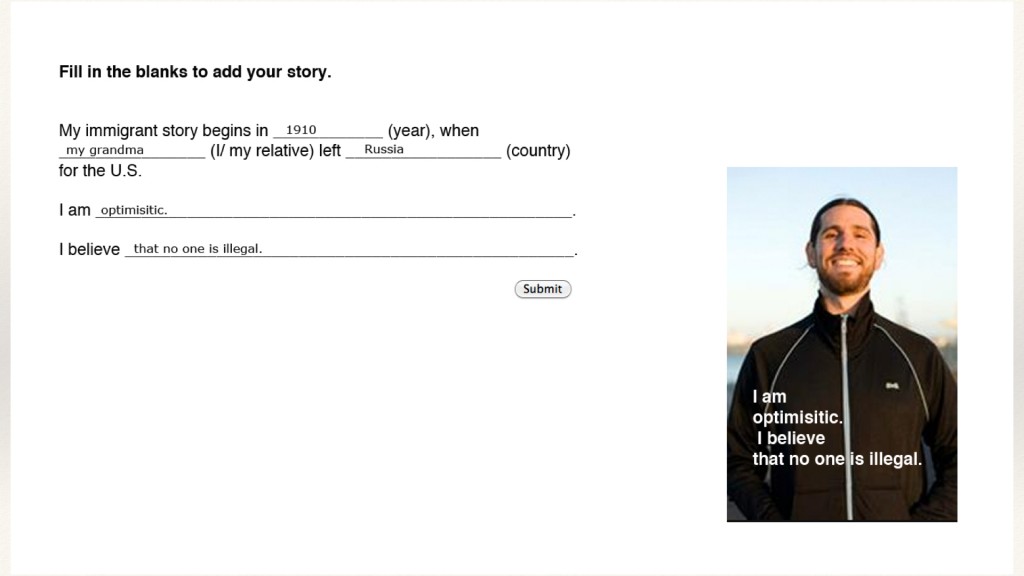

Idea: “My immigrant story begins in ____ when ___ came to _____.” Then user attaches a photo. Then you have the ability to tag family members. The big problem with this design plan was, people don’t like to login via Facebook.

We found a designer who was also in a band and a bartender – she needed us to write it down. We gave her hand-drawn wireframes, which she mocked up in about four minutes.

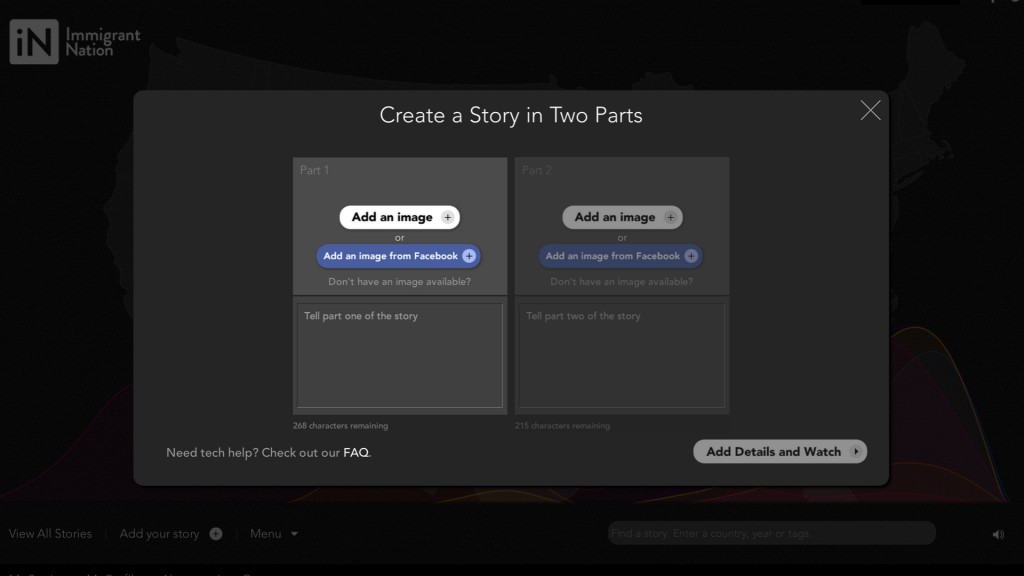

We had an idea of filling out an “I Beleve” statement, which was a bad idea. The platform that we built is simliar to this here, but we had originally put all the UGC steps in one page – add images, type text, add from Facebook. Many people didn’t have images so we linked to Creative Commons images.

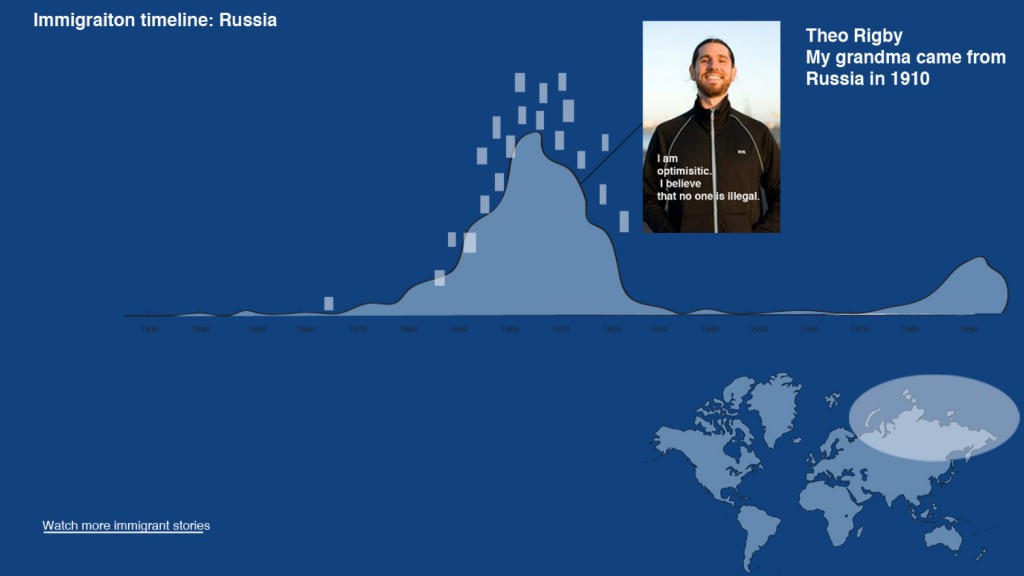

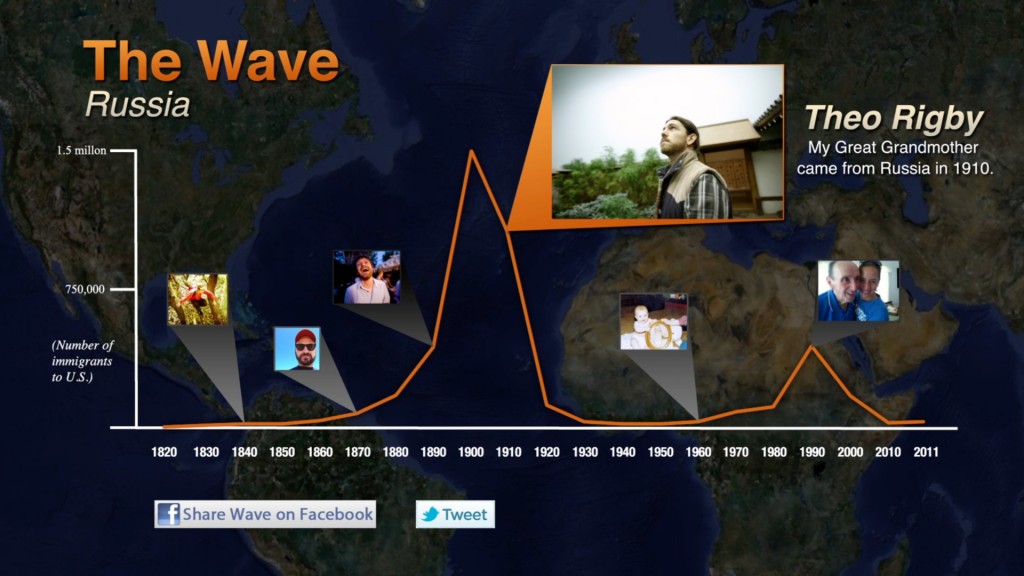

The Wave

Idea that your story gets placed on the wave of immigration from the story you chose. You can see how your story fits into the trajectory of immigration over the past 200 years.

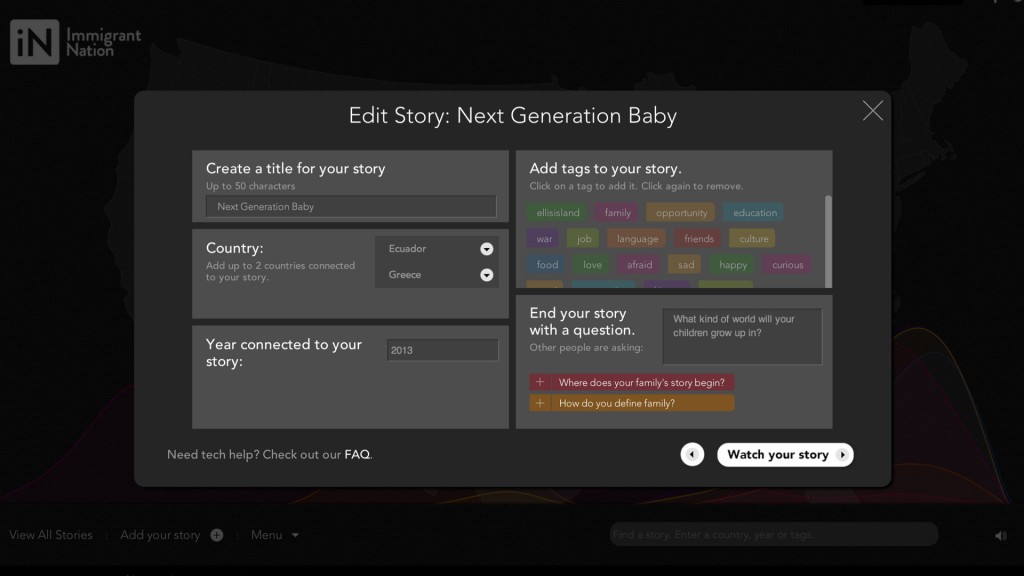

People create a title, choose two countries, a year and then the tags, which are really important. We want people to tell stories about identity and culture, so we wanted to bring the tags up to capture those things. You end your story with a question, which drives the process of the platform. You’re posed with a question and asked to answer.

The mockup we made in After Effects got us so far, because people actually got it. Whether it was possible to make that or not, people got it. That pushed the project so far forward.

When we got to HotHacks (organized by Mozilla and HotDocs), we talked to a real developer from Mozilla and we asked “Could we make this happen?” He said, “No. You might be able to make a few things happen.” We massively triaged. This was the first time my producing partner Kate and I had done coding and development.

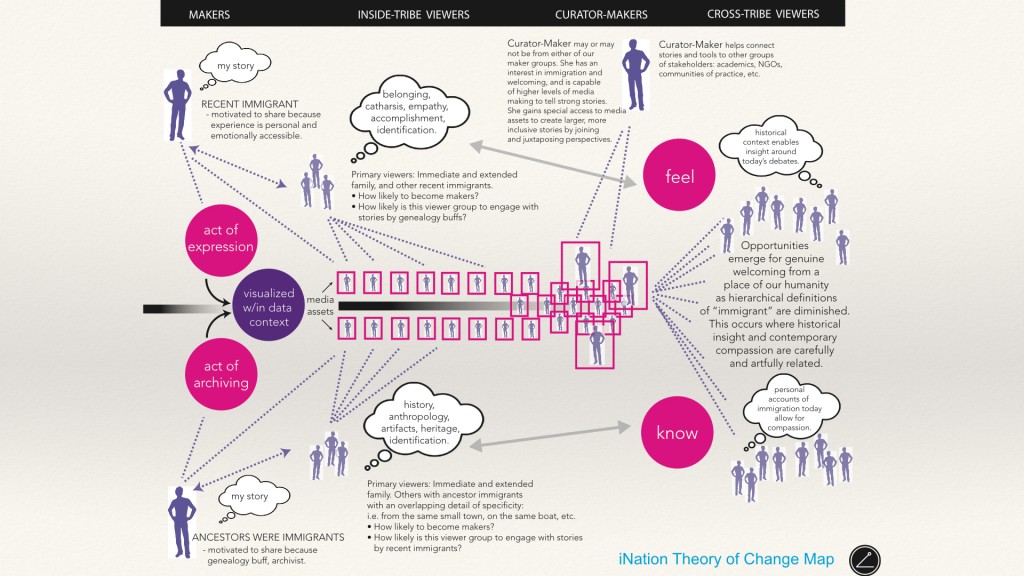

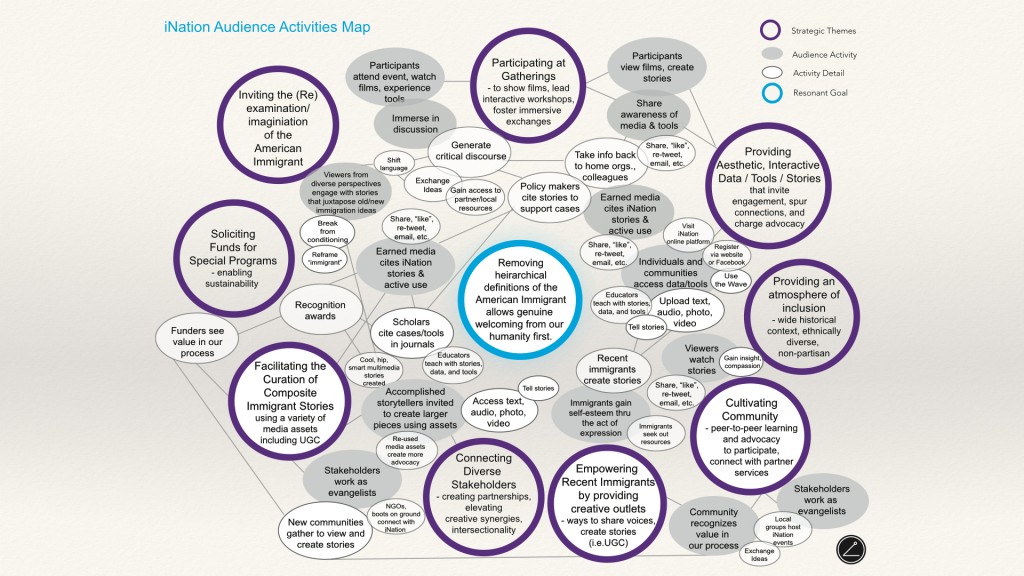

Then we connected with a systems thinking strategist, who created these maps of audience coming from different places and going through different user flows. “Acts of Expression” to “Acts of Archiving.”

We also created a mindmap. At the center is the phrase: “Removing hierarchical definitions of the American Immigrant allows genuine welcoming from our humanity first.”

This is our Theory of Change document. Looking at this today, it’s phenomenal how right this is. It highlights the differences between making a traditional feature film. There are so many more moving parts in an innately cross-platform thing.

The Target Audience

– Who’s going to use this?

– Where are they?

– How will they use it?

Dreamers, Educators

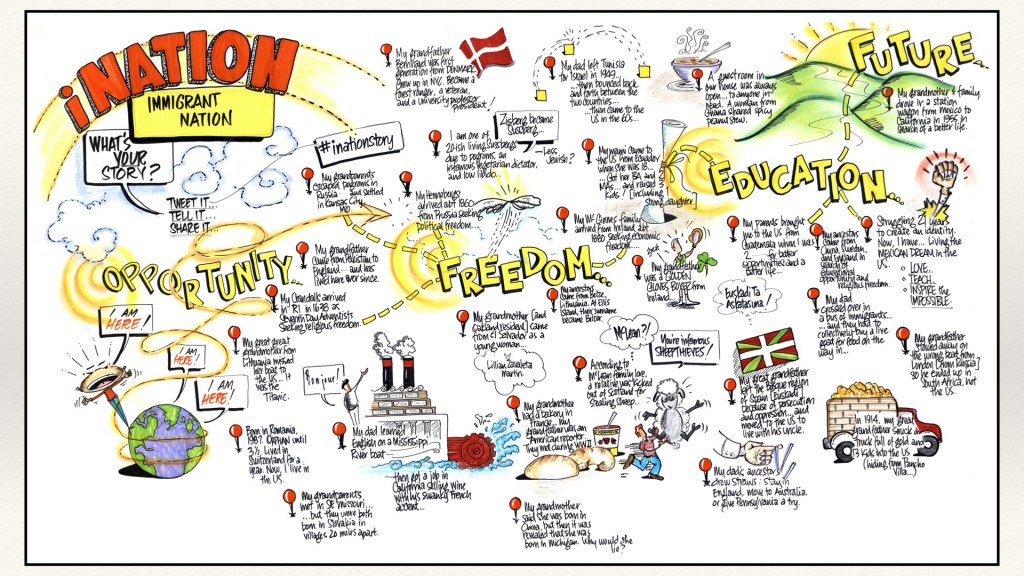

We didn’t have a platform yet but we started doing live events. We screened our film and asked people to share stories digitally. Our illustrator created murals to visualize those stories in a live environment. At schools, students would create their story and then stand up and share in front of their peers.

We started seeing where are “the sticky points.” Who’s connecting and where and why? We asked people pointed questions like “who is going to take care of the people you love?” and asked them to respond.

Then we met our developers, our knights in shaining armor. Mike Knowlton from StoryCode and Murmur. They’re in NYC, we’re in San Francisco. So we started chipping away at this thing in Google Hangout after Google Hangout.

We talked a lot about: Art vs Utility, Films vs UGC, Passive vs Active

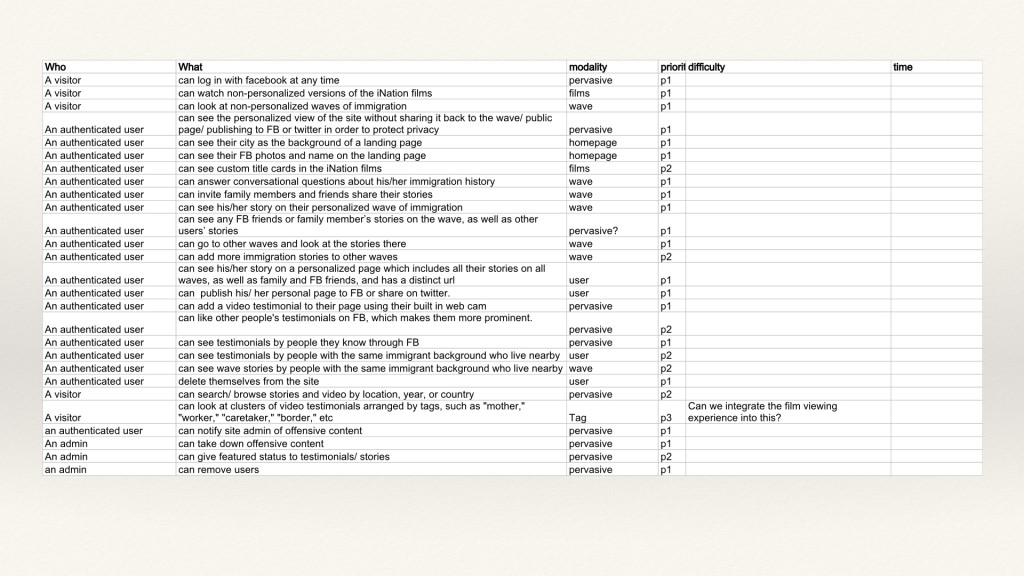

We had professionals make wireframes. We made lists of what an authenticated user could do, a visitor, an admin, etc.

Design. Build. Beta.

We thought the beta would be the final thing, and then we realized, “This is definitely a beta.” We launched a beta project, and stayed there for five months.

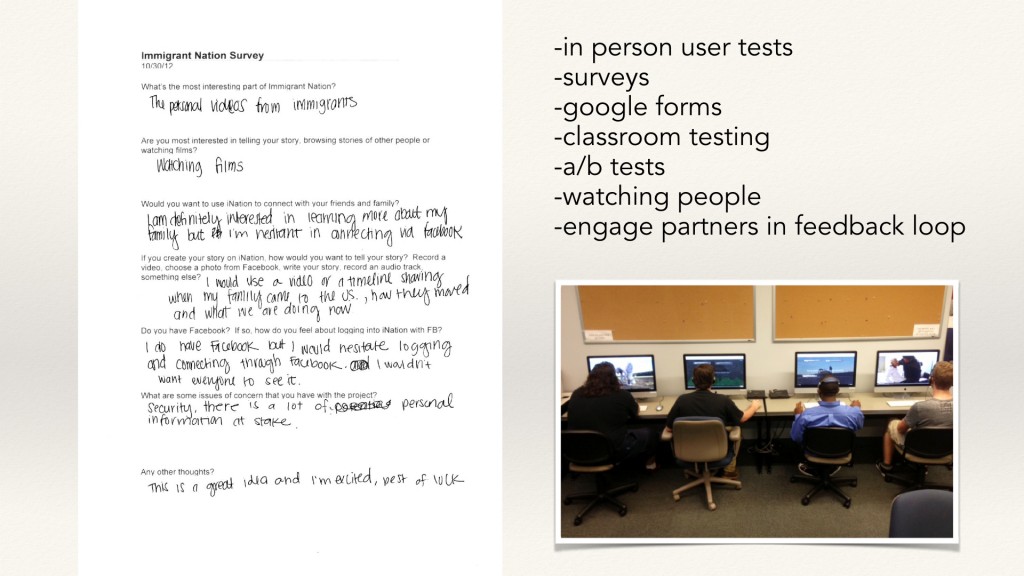

Beta phase enabled us to test and test and test. In every way imaginable: we watched people navigate it. A/B tests. Surveys. Screen recording. Google forms. We surveyed our partners, we’re still developing and we want your input. Engaigng partners from the very beginning was incredibly helfpul.

Phase Two Build

https://www.immigrant-nation.com/

There’s a teaser intro to the site. Then we focused more on the user generated stories at the resting state. These are stories created by users, two images and two bodies of text. It’s a simple way to tell your story that hopefully doesn’t set the bar too high or too low. Then the user poses a question to the audience, and people respond. We just launched 2 weeks ago and its interesting to see how many people create stories, how many people answer questions, and how many just lurk and consume.

The expected paradigm is totally true. Very few people tell stories, but a lot of people put a lot of thought into responding to these questions. After launching the project, it’s kind of hard to feel the pulse of whether its working or not. Its interesting to see how much energy they put into responding. This is an early success of the project.

We also have the films up on the site. After the first scene, it goes to a question. Ex. “Who will take care of the people you love?” Then you can add your thoughts, answer the question and take part.

Two weeks ago we launched by taking over the lobby at Ellis Island. Two days of live events. Big social media push and traditional press push, launch party. There is no Sundance Premiere for us, no big traditional festival way to premiere. We just had to make it up. We decided to do it in NYC at the biggest immigration symbol in the country, in line with Tribeca, and let’s have a big party, too. 100+ international high school groups, a big adult ESL class. We experienced the power of personal stories and oral histories told in the flesh. We had people tweet resposes, we created a mural, Project NannyVan came to the launch party. We went to TFI Interactive and asked people to Tweet responses to the quetsion “What does home mean to you?” We created a 10 foot mural from people’s tweets.

Now what?

We want to partner with people who will use this (educators etc.) in a way that’s sustainable, that doesn’t require us to create a massive event. Partner with National / Regional orgs. Provide a set of iNation tools to be used in a repeated and sustainable way. Create a space for the project to take on its own organically growing life.

Continue building the platform: installation, mobile, tablet, multi-lingual.

Q&A

Q: How do your subjects feel about your films? How do you create an entry point for Native Americans, or to deal with slavery?

Theo: I tend to make movies that make people cry. These are films that are hard to watch, but I hope that there is a univeral appreciation for these stories. Native American and African American stories were paramount from the beginning. How do we make this for a teacher who has a very diverse student body, how do we make it so no one feels left out? So it’s not, ‘I don’t have a story.”

I’ve had that reaction, and a high school kid will say, “I don’t have a story.” A lot of it has to do with framing, having someone who is sensitive these issues, couching it in a certain context. It takes a skill facilitator to talk about forced migration and slavery, anyway, in any case, and I had a Native American come up to me looking at the mural, and he said, “Well, my people have been here for 10,000 years. Settlers came and killed us off, there are only 70 left.” That’s an incredibly valuable story to be a part of our immigrant history.

We want people to find their wave, Native American wave. These are really tough and tricky and part of the story.

Q: I’m curious about some of the pitfalls, or what’s involved creatively in going from linear storytelling to nonlinear storytelling. The process, thinking about things differently.

Theo: I think I’ve never been a nonlinear storyteller. I started as a photographer, and very quickly the still photographs were too silent. So I started recording interviews. Then I started using early technology (miniDisc) to marry the two. I started there, then started recording moving image and adding that. But I get your question, and I guess, I mean I think at times its overwhelming because there are so many moving parts and so many directions you can go. When you’re making a linear story, there’s only one direction you can go. And then it stops. And you premiere at Sundance and play on HBO and sell a million DVDs.

I think mostly it’s — the difficulty is deciding where to put your limited resources and finding where to go next. Where is this gaining traction? How can we go there, and do it in a way that’s engaging and gains trust. There are many “Tell your immigration story” projects. The White House has one. Define America has one. Dream is Now has one.

How do you appeal to an audience to make them see you as someone worthwhile and worth trusting.

It’s important to lean on a range of advisors, to help you keep the blinders on to a degree, and not be consumed by all the options at one time. That’s been the most challenging piece of this whole process.