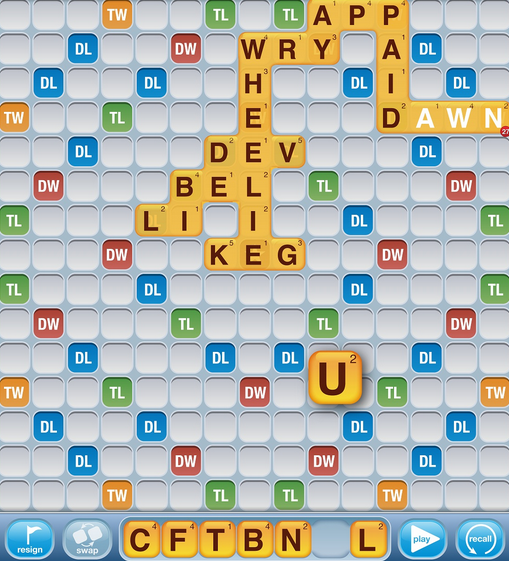

05 Jun Learning from Words With Friends

I have a confession. Like Alec Baldwin and many other Americans, I’ve been sucked into Zynga’s mobile game Words With Friends. Words, and its sister game, Scramble With Friends are examples of the phenomenon NYU’s Jesper Juul has called “casual games.” A self-identified gamer, Juul discovered casual games when friends who’d had limited interest in video games suddenly began playing:

All the games I enjoyed, such as real-time strategy games, I wanted to get people to play them but… it was very daunting for them. Then, suddenly at the same time you had the explosion of music games and the appearance of the Nintendo Wii and the success of downloadable games and games in browsers. Suddenly, all those friends and family who hadn’t really been playing games… wanted to play Wii bowling and they liked playing games in their browsers — and by now on their cellphones. It seemed that most of that barrier that existed to prevent people from playing video games was gone. (USA Today)

Casual games like Words With Friends, Wii Bowling, and Fruit Ninja are characterized by simplicity and accessibility. The barriers to entry are low. Controls are intuitive. Narrative situations understandable. And the time demands are limited. According to Juul,

You can play most of them for five minutes. You can play just one song on Rock Band, if that is what you want. But they allow you to play for five hours. They are more flexible about fitting into your life. (USA Today)

Casual games offer bite-sized experiences. Many users, myself included, like them because they’re a short break — a few minutes tops. It’s a diversion pre-packaged for today’s over-scheduled lifestyles. As Juul notes, there are always exceptions to the rule (in this case, communities of “casual” gamers who spend 20 hours a week playing games like Bejewled), but for the most part, casual games attract audiences by demanding little time or skill. They are short, pleasing, self-contained experiences.

‘Immersion’ has become a familiar buzzword in new media circles. Interactive media in general, and games in particular, are credited with the ability to create immersive experiences. Transmedia narratives, spread across multiple platforms, give people the opportunity to immerse themselves in a story world.

There’s no denying that immersion is desirable. Many of us interested in media making remember that first time (and the many times after) we were swept up by a story. But is immersion the right answer in all cases? If we think about interactive media as a tool for creating immersive experiences, what kind of narratives and platforms are we eliminating offhand?

When Gerry Flahive, producer of the National Film Board of Canada’s HIGHRISE project, visited MIT this past spring for the New Arts of Documentary summit, he said that visitors spent an average of seven minutes on HIGHRISE’s sites (albeit with return visits). HIGHRISE offers a rich, immersive experience that users can come back to time and again. But if we measure this phenomenon in games terms, the projects seem to be consumed in a pattern more akin to casual Words With Friends than the highly immersive World of Warcraft, for instance. Visitors take in small chunks of story, whenever they can fit it into their busy schedules.

Undoubtedly, filmmakers have a lot to learn from “immersive” elements of games. But games aren’t necessarily immersive, and so-called “casual games” are popular in part because they don’t demand total attention. I bring up this example to suggest that transmedia and interactive narratives aren’t necessarily immersive either. They can generate deep interest in users, but they don’t have to. Despite the popularity of sites like YouTube, built on casual viewing, the idea of “casual” web-based narratives seem to have received less attention than their immersive counterparts.

There are many types of audiences, who have different relationships to their entertainment content. When I worked in museum exhibition development, we broke our visitors into three general groups – waders, swimmers, and divers. The divers would look at nearly every artifact and read most captions, the swimmers would pick and choose, and the waders breezed through an exhibition in minutes. Put simply: people consumed content differently.

In a perfect world, we’d create stories that both waders and divers can enjoy. But while immersion can be a powerful draw (and seems to be an essential part of the experience that the “divers”-type craves), it can also be a barrier to entry. Juul’s friends had no desire to play time-demanding videogames with specialized mechanics. The skill it takes to successfully play some hardcore games (an element that attracts serious gamers) can make them unintelligible to casual users.

What can web filmmakers learn from the casual games phenomenon? Is there a future for “casual docs,” designed to be consumed in a bite sized way? How can filmmakers shape projects for casual viewers?

In other words, what can we learn from Words With Friends?

Katie Edgerton/MIT